“Beauty can be provocative and it complicates everything. It’s a way to transcend the tragedy—to challenge it.”

A PROCESS OF BECOMING

Introduction by Kathryn Harrison, July 18th, 2017

By definition, unconditional love is boundless. When extended to a loved one with a drug addiction, however, the side effects can be deeply toxic. At the forefront of my family work are these complexities of addiction, disease, and mental illness, alongside their relationship with the human condition. I was recently discussing these realities with my mother, who is currently raising my brother's infant son after both he and his girlfriend relapsed less than three months after his birth. We shared the fear of every disappearance, every phone call, every court date. As my mother's health continues to falter, I am filled with anxiety knowing I will soon be departing to complete my degree at Yale. Her total gastrectomy was only last year but, due to lupus, her body fights any progress. My brother's addiction and behavior prohibits my mother from necessary rest and healing. This discord ripples through my family like the waves preceding a tsunami. No one is left untouched—you are forced to swim otherwise you drown. Nothing is more difficult than to understand him. I have always feared that if I did not help, it would only get worse, but as the battles continue, I realize I sometimes lose focus on living my own life. Learning the differences between self-care and selfishness is tough. To me, life is a process of becoming. No matter how much I fear things will fall apart, all of nature is in motion. Combine schizophrenia; intermittent explosive disorder; opiate, meth, and crack addiction; chronic illness; and the birth of a baby, and one has a more realistic picture of my family's current state. It's not easy to define. I feel it in my heart. The following conversation took place less than eight weeks ago, when we were once celebrating sobriety, stability, and hope for the future.

By definition, unconditional love is boundless. When extended to a loved one with a drug addiction, however, the side effects can be deeply toxic. At the forefront of my family work are these complexities of addiction, disease, and mental illness, alongside their relationship with the human condition. I was recently discussing these realities with my mother, who is currently raising my brother's infant son after both he and his girlfriend relapsed less than three months after his birth. We shared the fear of every disappearance, every phone call, every court date. As my mother's health continues to falter, I am filled with anxiety knowing I will soon be departing to complete my degree at Yale. Her total gastrectomy was only last year but, due to lupus, her body fights any progress. My brother's addiction and behavior prohibits my mother from necessary rest and healing. This discord ripples through my family like the waves preceding a tsunami. No one is left untouched—you are forced to swim otherwise you drown. Nothing is more difficult than to understand him. I have always feared that if I did not help, it would only get worse, but as the battles continue, I realize I sometimes lose focus on living my own life. Learning the differences between self-care and selfishness is tough. To me, life is a process of becoming. No matter how much I fear things will fall apart, all of nature is in motion. Combine schizophrenia; intermittent explosive disorder; opiate, meth, and crack addiction; chronic illness; and the birth of a baby, and one has a more realistic picture of my family's current state. It's not easy to define. I feel it in my heart. The following conversation took place less than eight weeks ago, when we were once celebrating sobriety, stability, and hope for the future.

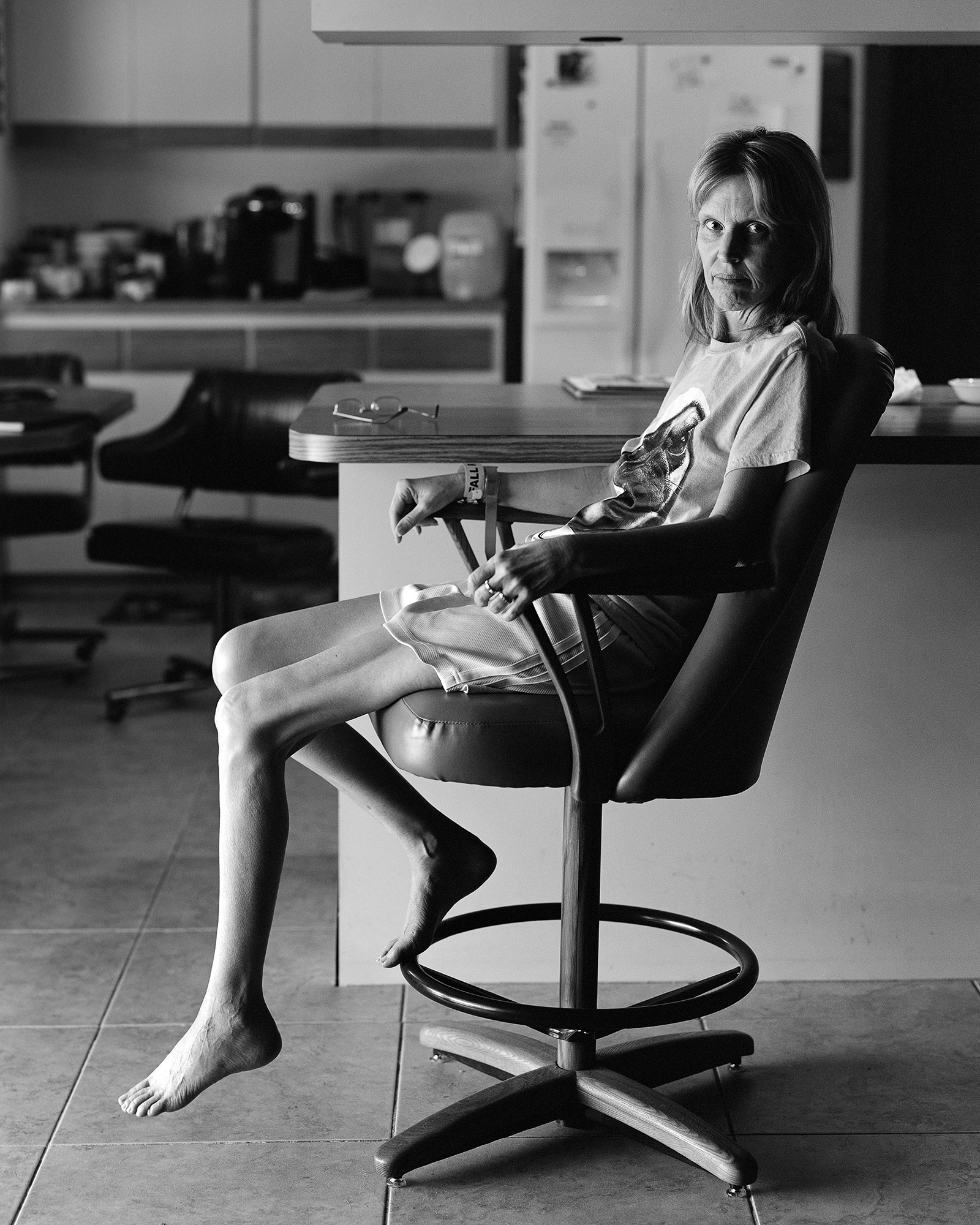

Kathryn Harrison, Full Circle, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Conversation between Kathryn Harrison and Anna Shimshak, April 17, 2017

Anna You mentioned trust in terms of your family allowing you to photograph them. Allowing yourself to be photographed is a big enough feat, but allowing yourself to be photographed when you know your identity speaks to the larger issues of mental illness and drug abuse in a photograph is another challenge. I guess, how do you deal with 1.) the issue of trust with your family and 2.) the issue of photographing your family with the intent to speak to these larger issues of the reality that you are dealing with as a vehicle to a larger discussion?

Kathryn There is a lot at stake photographing my family, and sometimes the risk of them being humiliated or ridiculed or bullied paralyzes me. The uncertainty is difficult to accept. But we understand that we are in it together. By sharing our personal experiences, we help each other move forward. I feel like the only way I can make work accessible is to show that I have been through it, even if I understand it in my own way.

Anna You’ve told me that part of the reason why your family allows you to take these pictures is to help people and to serve this larger purpose of awareness. When you photograph, especially in the moment of making the pictures, do you think of your family members not just as themselves, but also as these archetypes or icons of a larger issue? How does that affect the way you make an image?

Kathryn My family shares similar triumphs and troubles with other families all over the world. I worry about representation and visibility constantly but not while I’m making an image. I can’t or it wouldn’t be honest.

Anna You mentioned trust in terms of your family allowing you to photograph them. Allowing yourself to be photographed is a big enough feat, but allowing yourself to be photographed when you know your identity speaks to the larger issues of mental illness and drug abuse in a photograph is another challenge. I guess, how do you deal with 1.) the issue of trust with your family and 2.) the issue of photographing your family with the intent to speak to these larger issues of the reality that you are dealing with as a vehicle to a larger discussion?

Kathryn There is a lot at stake photographing my family, and sometimes the risk of them being humiliated or ridiculed or bullied paralyzes me. The uncertainty is difficult to accept. But we understand that we are in it together. By sharing our personal experiences, we help each other move forward. I feel like the only way I can make work accessible is to show that I have been through it, even if I understand it in my own way.

Anna You’ve told me that part of the reason why your family allows you to take these pictures is to help people and to serve this larger purpose of awareness. When you photograph, especially in the moment of making the pictures, do you think of your family members not just as themselves, but also as these archetypes or icons of a larger issue? How does that affect the way you make an image?

Kathryn My family shares similar triumphs and troubles with other families all over the world. I worry about representation and visibility constantly but not while I’m making an image. I can’t or it wouldn’t be honest.

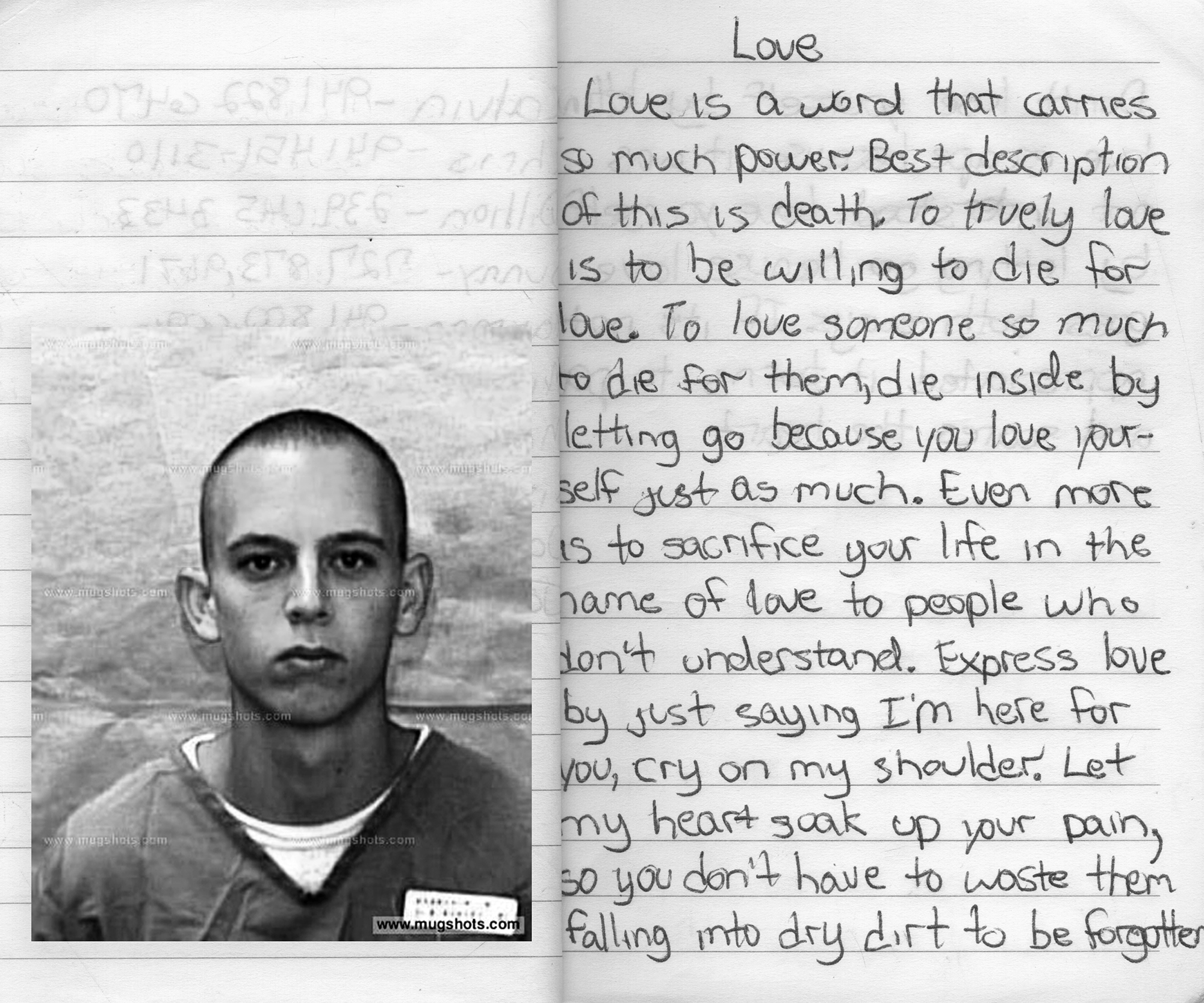

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Anna Do you think there are ways in which people with mental disabilities, drug abuse, and addiction are classified within a larger social context in a way that there is a stigma around their representation and even their existence? We tend to want to hide these people and not really deal with it as a sort of failing of social services. When you make this work being about this larger picture, how does that impact your interpretation in understanding this preexisting language of depiction for people within this category?

Kathryn Absolutely. I don't make these images with a raised fist. Although there has been a great deal of work made around the family and these larger social issues, there is still possibility for connection, to encourage caring. There are still stories to be told. I try not to let preexisting representations keep me from trying something. I have been very clear with myself and my family regarding what I don't want to show. The work is not exclusively political—it permeates.

Anna Do you see your brother in these people?

Kathryn In a way.

Anna Can you elaborate?

Kathryn Absolutely. I don't make these images with a raised fist. Although there has been a great deal of work made around the family and these larger social issues, there is still possibility for connection, to encourage caring. There are still stories to be told. I try not to let preexisting representations keep me from trying something. I have been very clear with myself and my family regarding what I don't want to show. The work is not exclusively political—it permeates.

Anna Do you see your brother in these people?

Kathryn In a way.

Anna Can you elaborate?

Kathryn Harrison, (both) Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Kathryn My brother and I are only two years apart. I watched and learned as the younger sibling. Siblings of schizophrenics (as well as other illnesses and disabilities) often feel never-ending waves of guilt, anger, and shame for being the “normal” one. “Why him and not me?” You know, generally the longest relationships in life are between siblings. He struggles in similar ways that I do but also in ways that I will never truly grasp. I see my brother everywhere and nowhere—in gesture, behavior, the way someone may blink or hold a cigarette left-handed.

Anna There is always the criticism of photography that it is innately exploitative. I personally have a very tumultuous response to that classification because I think it’s overly simplistic, but I guess for you there’s a sort of haven in photography, but it’s also this moralistic purpose. You are aiming for a higher truth or exposure of something through photography. Being the person behind the camera and also the caretaker can be disparate. How do you reconcile those two roles? Are they even disparate? The idea of being in control as a photographer and then responsible for your family, that is.

Anna There is always the criticism of photography that it is innately exploitative. I personally have a very tumultuous response to that classification because I think it’s overly simplistic, but I guess for you there’s a sort of haven in photography, but it’s also this moralistic purpose. You are aiming for a higher truth or exposure of something through photography. Being the person behind the camera and also the caretaker can be disparate. How do you reconcile those two roles? Are they even disparate? The idea of being in control as a photographer and then responsible for your family, that is.

Kathryn Harrison, Ray and Cherice, Sarasota, Florida, 2016

Kathryn I could not have one without the other. Since I was a child I have been obsessed with my mother’s plethora of snapshots, rearranging them in various ways to talk about things that are difficult to say. I’m interested in the idea that pictures can make you feel something, something complex. Photography is my haven—it allows me to transcend.

Anna Do you think it’s about control? If you can visually regulate what you’re seeing, then you could almost realize the pictures you’re making. If you could photograph your brother in a way that shows another side of him or allows him to become this other person in front of the camera, then maybe he could become that? Or is it that at all?

Kathryn In the past I thought I could “save” him, and I tried. I didn’t want him to suffer. As a sister, I had to face the reality that this is part of who he is. Control certainly plays a part in the work, me with him and him with me. We push each other’s boundaries but there is always love.

Anna Is it fair to say that so much of your bonding with your brother is predicated on this photographic relationship? That photography is the vehicle through which you both can meet in a sort of commonplace?

Kathryn I’d say so. I think he would agree too. We are very different people, but we both want a stronger relationship. Collaboration brings us closer. We both bring ideas to the table.

Anna Why do you think he likes being photographed?

Kathryn He has told me of his aspirations to help other people struggling with addiction and mental illness. He wants to tell his story. I think he also wants to feel heard and to be seen.

Anna Is it fair to say that so much of your bonding with your brother is predicated on this photographic relationship? That photography is the vehicle through which you both can meet in a sort of commonplace?

Kathryn I’d say so. I think he would agree too. We are very different people, but we both want a stronger relationship. Collaboration brings us closer. We both bring ideas to the table.

Anna Why do you think he likes being photographed?

Kathryn He has told me of his aspirations to help other people struggling with addiction and mental illness. He wants to tell his story. I think he also wants to feel heard and to be seen.

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Anna Do you think he sees himself more clearly through your pictures or a person he wants to be?

Kathryn I hope the pictures help him see how far he has come, to serve as reminders. Due to his multiple personalities combined with drug use, sometimes he isn’t aware of who is in the photograph. He functions in cycles where the tides shift unexpectedly.

Anna A hyper-refraction almost of his personality. You’ve mentioned that he’s photographed you. Can you talk about that reversal in dynamic?

Kathryn I haven’t shown them yet. When I sense he’s feeling uneasy or uncomfortable I’ll switch spots with him. Sometimes he just wants to take my picture though. Often I’m in mid-sentence explaining where the shutter release is, my hair wrecked from the dark cloth. I think one day if I get enough of them I will show them.

Anna Would you set up a situation or body of work where it’s just him photographing you the way that you photographed him for years?

Kathryn If he wanted to, I wouldn’t be opposed to it.

Anna Have you ever photographed your mom and brother together?

Kathryn Not yet.

Kathryn I hope the pictures help him see how far he has come, to serve as reminders. Due to his multiple personalities combined with drug use, sometimes he isn’t aware of who is in the photograph. He functions in cycles where the tides shift unexpectedly.

Anna A hyper-refraction almost of his personality. You’ve mentioned that he’s photographed you. Can you talk about that reversal in dynamic?

Kathryn I haven’t shown them yet. When I sense he’s feeling uneasy or uncomfortable I’ll switch spots with him. Sometimes he just wants to take my picture though. Often I’m in mid-sentence explaining where the shutter release is, my hair wrecked from the dark cloth. I think one day if I get enough of them I will show them.

Anna Would you set up a situation or body of work where it’s just him photographing you the way that you photographed him for years?

Kathryn If he wanted to, I wouldn’t be opposed to it.

Anna Have you ever photographed your mom and brother together?

Kathryn Not yet.

Kathryn Harrison, (both) Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Anna Switching gears a little bit—you photographed your mom through her health struggles and captured that level of intimacy and vulnerability. That is pretty amazing in terms of what she has given to you. When you take those photographs, there is the one way that you see them as a picture maker and another as a daughter and someone who understands her body because in many ways you are her sort of doppelganger or “mini-me.” How is it for your brother or other family members to see those pictures and see your mom the way that you see her and experiencing what she’s going through?

Kathryn My mom is not a vulnerable woman to the outside world. She only lets me see those things, actually. My brother doesn’t know that side of her. Maybe he doesn’t want to see it. The only reason she let me photograph her like that was because she didn’t think she would survive long after her gastrectomy. Her body was failing and at the time it was only the two of us. My brother wasn’t around and he didn’t come to the hospital. It was really difficult. Ultimately, she gave me those photographs as a final gift. She knew how much I needed to make the pictures; it is how I cope. They were the toughest photographs I’ve ever made.

Kathryn My mom is not a vulnerable woman to the outside world. She only lets me see those things, actually. My brother doesn’t know that side of her. Maybe he doesn’t want to see it. The only reason she let me photograph her like that was because she didn’t think she would survive long after her gastrectomy. Her body was failing and at the time it was only the two of us. My brother wasn’t around and he didn’t come to the hospital. It was really difficult. Ultimately, she gave me those photographs as a final gift. She knew how much I needed to make the pictures; it is how I cope. They were the toughest photographs I’ve ever made.

Kathryn Harrison, Mom, Post-Gastrectomy, Sarasota, Florida, 2016

Anna I think rightly so…I guess this question of temporality is really present because…thinking about why we allow ourselves to be photographed and why we make pictures…visibility and so much of it is about capturing memory and showing something, knowing that there is a certain exposure that comes with it. Physically in the image itself it is an exposure, but also in the fact that you’re allowing something of yourself to be seen psychologically. There is a difference in the visibility of your brother and his desire to be photographed and your mom and only allowing herself to be photographed thinking that she would never see the pictures. I guess now that she has seen the pictures, you continue to photograph her, and she is getting better thankfully, how does that affect things now?

Kathryn When I show her the photographs, she gasps. She doesn’t like to appear weak or out of character, but she’s never asked me not to show them. I think the hospital bed photograph is the most difficult for her to live with. It is the photograph which embodies my overwhelming fear of things falling apart, quite literally.

Kathryn When I show her the photographs, she gasps. She doesn’t like to appear weak or out of character, but she’s never asked me not to show them. I think the hospital bed photograph is the most difficult for her to live with. It is the photograph which embodies my overwhelming fear of things falling apart, quite literally.

Anna The pictures are not not beautiful. I guess that is one of the things that is maybe so interesting… it’s a part of the complexity. The black and white pictures that you showed—they’re painterly and gorgeous in the way that they are rendered and her body is devastating but also beautifully rendered. I guess that leads me to ask the “Gregory Crewdson million dollar question,” “What role does beauty play?”

Kathryn Beauty can be provocative and it complicates everything. It’s a way to transcend the tragedy—to challenge it. I want to look, no matter how difficult. I want to see how strong she is. When I made the pictures I wanted to show her the way I saw her. I was terrified of losing her.

Anna Do you think that your photographic self and your daughter/sister self are separate?

Kathryn I don’t see my “selves” as separate but rather they push and pull.

Anna Do you photograph her as a daughter?

Kathryn I hope I do. I was a daughter first.

Kathryn Beauty can be provocative and it complicates everything. It’s a way to transcend the tragedy—to challenge it. I want to look, no matter how difficult. I want to see how strong she is. When I made the pictures I wanted to show her the way I saw her. I was terrified of losing her.

Anna Do you think that your photographic self and your daughter/sister self are separate?

Kathryn I don’t see my “selves” as separate but rather they push and pull.

Anna Do you photograph her as a daughter?

Kathryn I hope I do. I was a daughter first.

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Anna I’m just curious. I think about when I photograph, there is a sort of alter ego, but my photographic self is far more willing to take a risk and live on the edge in a way that my normal every day, especially my familial self, would never do.

Kathryn Yes, I can see that. You have an ability to work under the radar, incognito, in an underground world with extremely limited access. I always wonder what you think about it, how you get yourself in the situations that you do.

Anna I mean, I could ask you the same thing! When you photograph this and are aware of the very immediate reality of the family and these larger political and social issues…what goes on in your mind when you’re shooting? Are you trying to layer all of these issues intentionally or do you allow them to come more intuitively? How does it affect your process?

Kathryn These issues exist all around us but it’s the matter of actually making the pictures. Certain truths come to the surface over time. I wonder how I can tell the story better, what I am missing. Generally, I make a shooting script of ideas or points, and other times I go for a walk and there it is—the picture—and then I won’t look at it for weeks. I need time to consider it, and I have to write about it. Writing is tremendously helpful, and private.. The process and ability to articulate thoughts into language.

Anna Do you think about your pictures sometimes as a sort of elevated version of a family photo? Do you think that one day you will use these to talk about your family? Or do you think they will remain separate as art or are they not inseparable?

Kathryn I don’t know yet. I see my life as my art and my art as my life.

Anna I’m wondering in 15 years how you will photograph your children, if you have them, or your spouse/partner. Do you live in a Sally Mann world with her relationship to the permeability between the two? Or for you, is there a time to make art and a time to be within the family?

Kathryn I’m sure they wish they could be around me without me looking for the next picture.

Anna Do you think you will ever be done with it then?

Kathryn In the big picture, no, but I do take breaks from it when it is no longer productive or healthy.

Kathryn Yes, I can see that. You have an ability to work under the radar, incognito, in an underground world with extremely limited access. I always wonder what you think about it, how you get yourself in the situations that you do.

Anna I mean, I could ask you the same thing! When you photograph this and are aware of the very immediate reality of the family and these larger political and social issues…what goes on in your mind when you’re shooting? Are you trying to layer all of these issues intentionally or do you allow them to come more intuitively? How does it affect your process?

Kathryn These issues exist all around us but it’s the matter of actually making the pictures. Certain truths come to the surface over time. I wonder how I can tell the story better, what I am missing. Generally, I make a shooting script of ideas or points, and other times I go for a walk and there it is—the picture—and then I won’t look at it for weeks. I need time to consider it, and I have to write about it. Writing is tremendously helpful, and private.. The process and ability to articulate thoughts into language.

Anna Do you think about your pictures sometimes as a sort of elevated version of a family photo? Do you think that one day you will use these to talk about your family? Or do you think they will remain separate as art or are they not inseparable?

Kathryn I don’t know yet. I see my life as my art and my art as my life.

Anna I’m wondering in 15 years how you will photograph your children, if you have them, or your spouse/partner. Do you live in a Sally Mann world with her relationship to the permeability between the two? Or for you, is there a time to make art and a time to be within the family?

Kathryn I’m sure they wish they could be around me without me looking for the next picture.

Anna Do you think you will ever be done with it then?

Kathryn In the big picture, no, but I do take breaks from it when it is no longer productive or healthy.

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2016

Anna Do you think it’s about death?

Kathryn It’s more about me hanging onto them as much as I can. I’ve had to face the reality of my mother dying from a very young age, that one day she wouldn’t come home. She taught us how to survive without her, but I never let go. Every surgery or procedure was trying and it never got easier. Now, we face the death of my brother. He refuses treatment despite his current state of health. We will all die one day, but I am not desensitized to death. I don’t think love and death cancel each other out—they coexist.

Anna A sort of preservation of the self—do you think you are trying to preserve a version of yourself as much as you are a version of them?

Kathryn I like to see how my pictures change—how I am changing as I take those pictures. I was talking about this with someone the other day. Often when you grow up in a very chaotic household, you become fixated on this need for control, but it’s an illusion. You know what has happened and you try to plan for things so there’s less chance to get hurt. But, I mean, that’s life. I think that is something I struggle with. Being open to being hurt…in life and with photographs.

Anna But you’ve also mentioned how people that you photograph become larger than themselves—how they become icons, and I wonder about the redemptive nature of portraiture. I wonder whether or not there is redemption—not in the profane sense—but if there is learning to be had or a revelation to be made, even if you’re photographing something horrible, difficult, ugly or grotesque, that there is learning or an awakening consciousness for the viewer. It’s not so much that you are changing the person’s life that you are photographing, but it’s more about a visibility that may be a greater purpose for the work.

Kathryn I think confronting the uncomfortable is a way to explore and reveal, not solely for the sake of suspense. I hope there is a greater purpose for the work as it starts living out in the world. A mentor once told me, “I can’t tell you what to care about,” and I feel that way when talking about my photographs. Despite struggling with the responsibility of the photographs, I haven’t stopped making them.

Kathryn It’s more about me hanging onto them as much as I can. I’ve had to face the reality of my mother dying from a very young age, that one day she wouldn’t come home. She taught us how to survive without her, but I never let go. Every surgery or procedure was trying and it never got easier. Now, we face the death of my brother. He refuses treatment despite his current state of health. We will all die one day, but I am not desensitized to death. I don’t think love and death cancel each other out—they coexist.

Anna A sort of preservation of the self—do you think you are trying to preserve a version of yourself as much as you are a version of them?

Kathryn I like to see how my pictures change—how I am changing as I take those pictures. I was talking about this with someone the other day. Often when you grow up in a very chaotic household, you become fixated on this need for control, but it’s an illusion. You know what has happened and you try to plan for things so there’s less chance to get hurt. But, I mean, that’s life. I think that is something I struggle with. Being open to being hurt…in life and with photographs.

Anna But you’ve also mentioned how people that you photograph become larger than themselves—how they become icons, and I wonder about the redemptive nature of portraiture. I wonder whether or not there is redemption—not in the profane sense—but if there is learning to be had or a revelation to be made, even if you’re photographing something horrible, difficult, ugly or grotesque, that there is learning or an awakening consciousness for the viewer. It’s not so much that you are changing the person’s life that you are photographing, but it’s more about a visibility that may be a greater purpose for the work.

Kathryn I think confronting the uncomfortable is a way to explore and reveal, not solely for the sake of suspense. I hope there is a greater purpose for the work as it starts living out in the world. A mentor once told me, “I can’t tell you what to care about,” and I feel that way when talking about my photographs. Despite struggling with the responsibility of the photographs, I haven’t stopped making them.

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2017

Anna I think about controversial work, especially given contemporary politics and how social justice concerns are dominant. I remember when I was a kid, my dad told me that growth does not happen without pain. Great art is not made from a place of complacency, a peaceful utopian vacuum. It’s made in struggle and controversy. As makers, we give birth to these things and create them and pour ourselves and our families and lives into them. They then do have lives themselves. Parents have children and the children become their own beings. In some ways, the work we make is like that as well. You set out to do one thing and then it takes on a life of its own. You can steer it, but…I don’t know. Maybe it shouldn’t be something that you are totally happy to live with. Do you feel that all that responsibility is on you?

Kathryn Yes, I am the maker, but I agree that once work becomes visible to the world it becomes something else, something out of our control. There is a lot of emotional risk involved. It’s not meant to be easy. I have access to these two disparate worlds, here at Yale and there in Florida, and through photography I am trying to find my place in both, reporting back and forth of what I know.

Anna Photography is redemptive for you in that way. It’s your way out and your way back. It allows you opportunity to achieve, but it is always a sort of bridge and heartstring to your home and family.

Kathryn Photography brings me in but also creates distance. It is the way I can learn and learn to let go.

Anna Do you feel like photography could be an outlet for anger?

Kathryn It’s a way for me to cope, but it also drives me to create from that difficult place. I feel that every time my brother steps in front of my camera he is showing me how much he loves me. If either one of us is angry, it’s in the picture.

Anna We mentioned earlier that there is such a stigma associated with mental health, homelessness, health problems, and especially women and health. The way that women can be treated pejoratively for being sick…we all see these people, but you are asking people to see them differently and with empathy. The pictures function on so many different levels. They beg to be seen. They seduce you to look and then show you a brutal honesty of things that transcend the immediate social issues and demand, on a fundamental level, empathy for another human being. Where do you ultimately see the work going? Where do you hope it will go?

Kathryn It won’t stop until it gets where it's going.

Kathryn Yes, I am the maker, but I agree that once work becomes visible to the world it becomes something else, something out of our control. There is a lot of emotional risk involved. It’s not meant to be easy. I have access to these two disparate worlds, here at Yale and there in Florida, and through photography I am trying to find my place in both, reporting back and forth of what I know.

Anna Photography is redemptive for you in that way. It’s your way out and your way back. It allows you opportunity to achieve, but it is always a sort of bridge and heartstring to your home and family.

Kathryn Photography brings me in but also creates distance. It is the way I can learn and learn to let go.

Anna Do you feel like photography could be an outlet for anger?

Kathryn It’s a way for me to cope, but it also drives me to create from that difficult place. I feel that every time my brother steps in front of my camera he is showing me how much he loves me. If either one of us is angry, it’s in the picture.

Anna We mentioned earlier that there is such a stigma associated with mental health, homelessness, health problems, and especially women and health. The way that women can be treated pejoratively for being sick…we all see these people, but you are asking people to see them differently and with empathy. The pictures function on so many different levels. They beg to be seen. They seduce you to look and then show you a brutal honesty of things that transcend the immediate social issues and demand, on a fundamental level, empathy for another human being. Where do you ultimately see the work going? Where do you hope it will go?

Kathryn It won’t stop until it gets where it's going.

︎