“I felt that if I was asking strangers to put themselves in front of the camera, it was only fair if I did the same myself.”

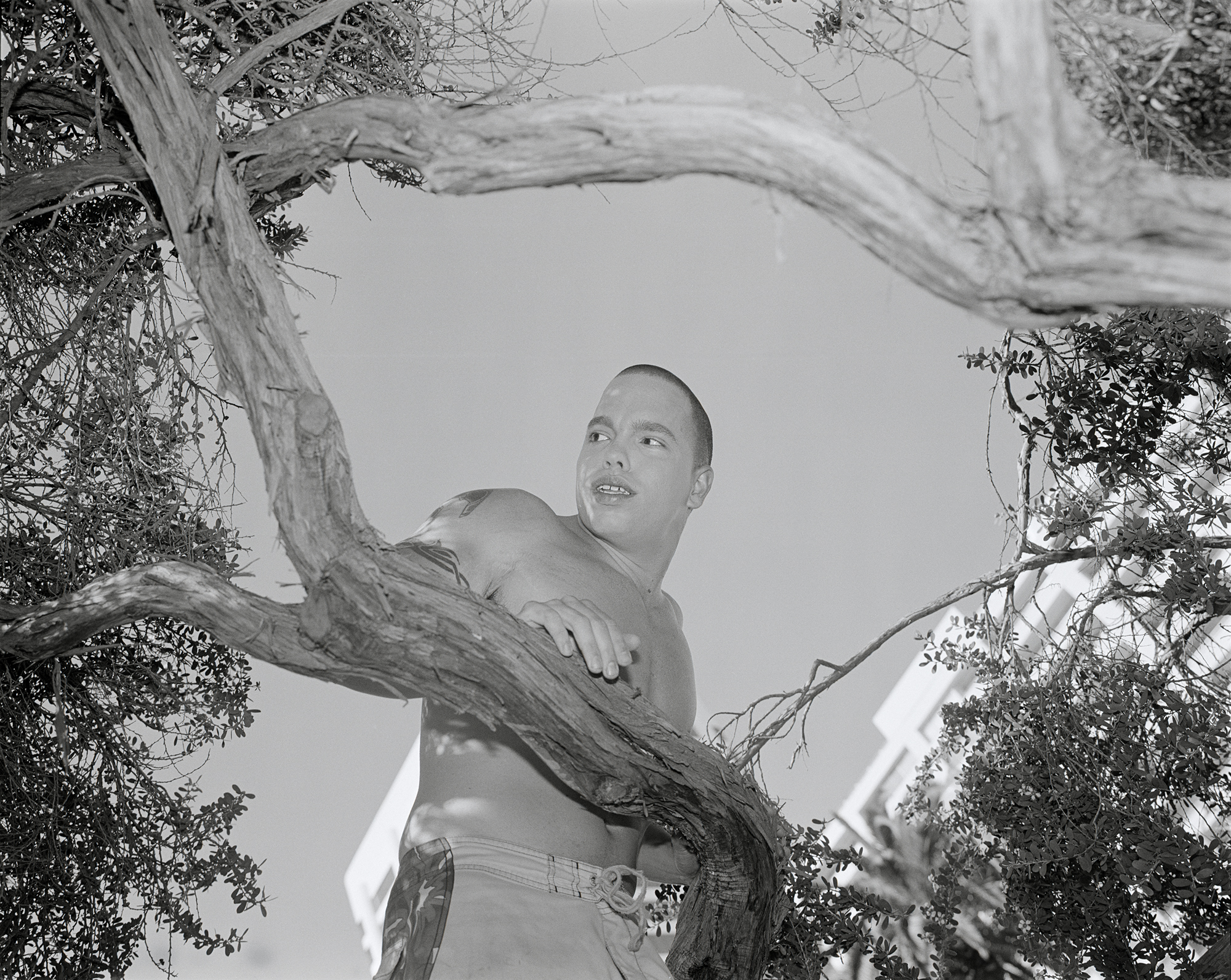

Rory Mulligan, Century Plant, 2010

LIKE A DOG TRACKING A SCENT

Nich Hance McElroy Although much of your early work feels like straight, observationally-based photography, you also—perhaps increasingly—employ staged portraits and self-portraiture. Based on your entry in The Photographer’s Playbook, I realize these portraits play an important role in your practice and pedagogy. In both aesthetics and mood, they’re a piece from the out-in-the-world work, but they represent a different way of operating. I want to understand the portrait work you do, and how it communicates with the more strictly observational work, which turns on (what feel like) chance encounters and your keen ability to read and render light. Is this an artificial distinction?

Rory Mulligan The portraits grew out of the observational work and the self-portraits from there. I was very conscious of the fact that my work fell into what was (this is back in 2007/8) considered a dead zone in contemporary photography. Work that was made out in the world with black and white film, uncontrived and perhaps most deadly of all: earnest.

Rory Mulligan The portraits grew out of the observational work and the self-portraits from there. I was very conscious of the fact that my work fell into what was (this is back in 2007/8) considered a dead zone in contemporary photography. Work that was made out in the world with black and white film, uncontrived and perhaps most deadly of all: earnest.

Rory Mulligan, Envelope, 2008

I was pulled out of this hazy adoration by the overdose of one of my oldest friends the summer before I started grad school. We had mostly lost touch by that point but it really shook me. We were inseparable for so long and I was about to go to Yale and he was dead. How can life diverge so quickly and so violently for two people once so entwined? This shifted my interests away from the anonymous figures and shapes of the city back home to the suburbs. I started to think about male bonding. Why was I trying so hard to fit into this boy’s club that never would’ve had me anyway? How exactly do I fit in with other men outside of art and photography? More pointedly, why don’t I?

The first portraits I ever made were taken inside Central Park at night. I solicited older gay men on craigslist as a heavy handed attempt to begin to fill in some gaps I felt missing from this specific strain of black and white photographic history. There was also a parallel to analog photography itself in the act of making these pictures. I was referencing cruising in the Ramble, an act that at this point was (almost entirely) obsolete. Something once exchanged through the immediate currency of corporeality was being usurped by digital technology. At this point Grindr didn’t exist, but Manhunt/craigslist/et al. did. It felt akin to the way photography itself had transitioned from such a hands-on craft to a problem that can be solved with buttons.

The first portraits I ever made were taken inside Central Park at night. I solicited older gay men on craigslist as a heavy handed attempt to begin to fill in some gaps I felt missing from this specific strain of black and white photographic history. There was also a parallel to analog photography itself in the act of making these pictures. I was referencing cruising in the Ramble, an act that at this point was (almost entirely) obsolete. Something once exchanged through the immediate currency of corporeality was being usurped by digital technology. At this point Grindr didn’t exist, but Manhunt/craigslist/et al. did. It felt akin to the way photography itself had transitioned from such a hands-on craft to a problem that can be solved with buttons.

Rory Mulligan, John, 2008

Rory Mulligan, Egg, 2009

Rory Mulligan, Tim, 2014

The self-portraits started happening at about the same time, and they were far less planned or thought out. I had never worked with models before, and the experience was a bit jarring and awkward. Just showing up with an idea is very different from knowing how to pose someone or get them comfortable in front of the camera. Questions about agency and exploitation were issues I had to consider more carefully now (though some of the work I made out on the streets is actually much more problematic in this regard). I felt that if I was asking strangers to put themselves in front of the camera, it was only fair if I did the same myself. I’m not sure this is sound moral equivalency, but it was a way for me to have a much clearer stake in the game. It also put my image and body in conversation with these other men and the world I photographed in a different, frankly imagined, context.

These three types of images began to blend together in edits and sequences to create some sort of language I was trying to build. Each process is very distinct, and the observational work was certainly where I felt most comfortable. The portraits added tension and a sense of unease. The self-portraits felt much more fluid and expressive and sometimes even performative. While I was trying to acknowledge my own specific references and influences within black and white photography and turn them on their head a bit, my discomfort with relating to other men sexually and emotionally at this point was equally important in the work. It’s not as if I rejected the dogma of the hetero white male street photographer to go play for the queer team of artists making work about lust, sex and identity; I was equally, if not more so, uncomfortable in that realm. I didn’t really belong anywhere in these different worlds so I had to make my own.

These three types of images began to blend together in edits and sequences to create some sort of language I was trying to build. Each process is very distinct, and the observational work was certainly where I felt most comfortable. The portraits added tension and a sense of unease. The self-portraits felt much more fluid and expressive and sometimes even performative. While I was trying to acknowledge my own specific references and influences within black and white photography and turn them on their head a bit, my discomfort with relating to other men sexually and emotionally at this point was equally important in the work. It’s not as if I rejected the dogma of the hetero white male street photographer to go play for the queer team of artists making work about lust, sex and identity; I was equally, if not more so, uncomfortable in that realm. I didn’t really belong anywhere in these different worlds so I had to make my own.

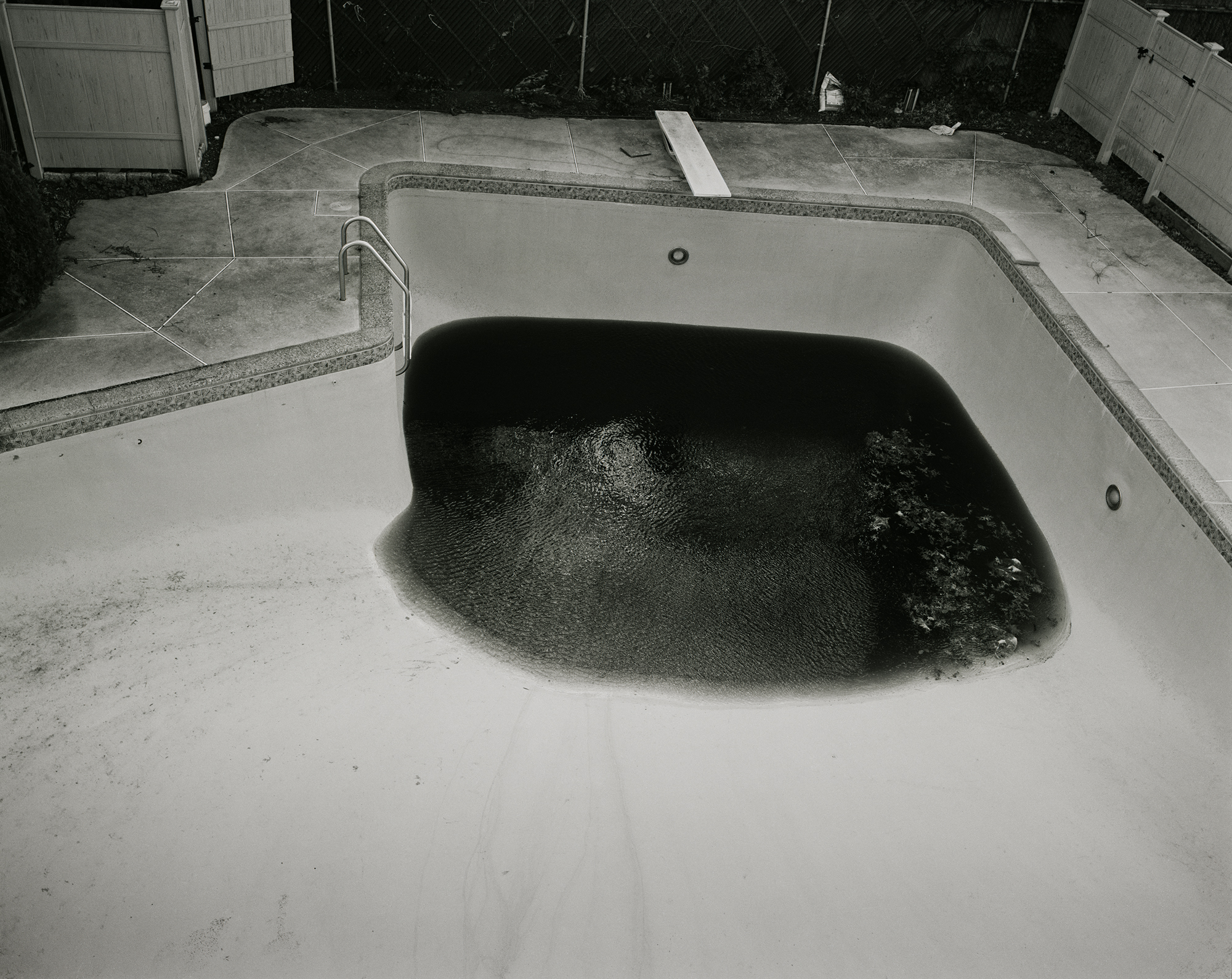

Rory Mulligan (from top), Floating, 2009; Pool, 2011

Nich The world that you’ve created for yourself reads as historically enmeshed, both in the conscious history-of-the-medium ways that you’ve acknowledged, but also in a particular kind of temporal collapse I sense while looking at your work. I’ve always felt that you conjure a mythological space within the contemporary settings you photograph—New York City, the northern suburbs, California. Those spaces are layered with an objective human history (“Cindy Timberwolf 12-30-71” written in cement) and, it seems, some subjective personal history. The same way you were looking for a vapor of what Papageorge found in Central Park, you’re attuned to another residue closer to home or in settings that feel more like your own. It’s a strange way to read historical details, but the things you look at frequently contain some ominous portent, which is where the mythological feeling comes from for me. They are mysteries and signs, and they foretell or rehearse something dark that’s happened, or will soon happen. I wonder: what do you think about this historical layering?

Rory I’m certainly interested in spaces and objects that feel so banal it’s as if they don’t even count in ‘history’, or at least they wouldn’t be recorded otherwise. I was having a conversation with a friend in my studio recently about this idea of spaces that contain some sort of charge via their historical importance. My current project deals with a place that is tangential but pertinent to a very notorious and violent chapter of history in this area (the Lower Hudson Valley of New York/New York’s outer boroughs). It’s very different from my older work in that this specificity to place occurs mostly outside of my personal biography. Anyway, his point was essentially that history occurs everywhere at any moment and we’re never aware of 99% of it. He pointed to a house outside the window and said that maybe something horrific has happened there or will happen. Who knows? What I think he was saying was that it’s not really the physical location of an event that matters and, going further, the overwhelming tsunami of occurrences happening every single second of every day leaves us with some pretty wide gaps in what we know and the stories we even have the choice to tell.

When I returned to the suburbs to make my work, I was very much like a dog tracking a scent, except the body had already been discovered. I wasn’t trying to solve a murder or pinpoint the moment things slid off a cliff for my friend. I wasn’t sure what I was doing; I just knew I needed to be there and to photograph. When I made this work, I had this rule that I could only photograph places I could walk to from my parents’ house. I only have one recurring dream and it takes place in an area along the Bronx River that I returned to again and again to shoot. The river is drained and I’m walking in the mud when I start to notice snakes underfoot. First there are a couple and then they are everywhere, all sizes and types, slithering and rustling. There is a moment of exhilaration that something so wild could happen in such a defanged suburban landscape, but then the horror sets in.

My point is that it was the dream as much as the reality that I once inhabited this space with someone I loved who was now dead that drew me here. Which is more real? I’m drawn to sites and ideas that are considered dead or void but might register a gasp if you listen carefully enough. This makes things more difficult for me in trying to put together a body of work or even to figure out what exactly to photograph. I am tethered to spaces, but time is constantly erasing and regenerating what I want. Maybe I’m like a moth to the flame of disappointment. I’ve never had a subject that I can put in front of the camera and say, “Here it is!” Even when I think I do, it’s never really the thing itself. I truly am at war with the obvious, or at least I wouldn’t even know what to do with it if I saw it.

My point is that it was the dream as much as the reality that I once inhabited this space with someone I loved who was now dead that drew me here. Which is more real? I’m drawn to sites and ideas that are considered dead or void but might register a gasp if you listen carefully enough. This makes things more difficult for me in trying to put together a body of work or even to figure out what exactly to photograph. I am tethered to spaces, but time is constantly erasing and regenerating what I want. Maybe I’m like a moth to the flame of disappointment. I’ve never had a subject that I can put in front of the camera and say, “Here it is!” Even when I think I do, it’s never really the thing itself. I truly am at war with the obvious, or at least I wouldn’t even know what to do with it if I saw it.

Rory Mulligan, East River, 2008

Nich What you’re saying speaks to a part of what’s compelling about your work. It doesn’t come across as though you have an answer, or even a nominal subject, that you’re withholding from the viewer. Many of your photographs feel like remnants and portents, both of which can be frustrating to encounter if you’re looking for meaning in them, but they’re emotionally charged.

Another part of what I hear you saying is that you’re not a sculptor, or someone who works from a fixed idea that you then chisel out of the world. Instead, it seems like you’re interested in frisson—moments of affective intensity, like walking in the river bottom full of snakes. That seems in keeping with the street photography ethos, which prizes candid encounter. Is trying to fit these encounters into a more rigid structure a capitulation to the market, or does it represent a new, fertile way of working for you? How does the editing process bear down on this for you?

Another part of what I hear you saying is that you’re not a sculptor, or someone who works from a fixed idea that you then chisel out of the world. Instead, it seems like you’re interested in frisson—moments of affective intensity, like walking in the river bottom full of snakes. That seems in keeping with the street photography ethos, which prizes candid encounter. Is trying to fit these encounters into a more rigid structure a capitulation to the market, or does it represent a new, fertile way of working for you? How does the editing process bear down on this for you?

Rory The idea of meaning in photographs is certainly one that has always been secondary to the feeling I want them to produce, both through the content and the physical object of a silver gelatin print. This isn’t to say that my work doesn’t ‘mean’ anything and is just a pastiche of moody shoegazey imagery. The meaning largely comes through the editing for me. At the same time, editing just highlights what was either consciously or subconsciously within my objectives before and during shooting. All of the work we’re discussing here was made during a time when I would shoot quite a lot. I think this idea of quantity (shoot now, ask later) was certainly a remnant of the

street photography ethos in my practice.

The structures that I’ve created for myself when editing feel less like confines and more like spaces that provide the room to say what I need to say. One of the ways I’ve tried to distinguish myself from this tradition we’ve been discussing is through editing and sequencing. The idea of strings of images speaking to one another and adding up to something bigger than each piece is nothing new. Walker Evans and Robert Frank both figured this one out. From my perspective, both Evans and Frank have a very male point of view in their work: it feels objective (not to say enervated) and always outward looking. If we then look at Francesca Woodman, I think it’s fair to say her work has a very female point of view that looks inward while also reflecting how outward pressures and forces affect this inward gaze.

Rory Mulligan, Markus, 2009

Something that I’m aiming for in my work is the way Virginia Woolf describes the ideal mind in A Room of One’s Own as being androgynous: both man-womanly and woman-manly. What if Robert tried being Francesca and Francesca tried being Robert? It would probably be a mess and ultimately uninteresting, but these are two approaches to the world that are intrinsic to my description of it. It’s the matter of melding them together in the editing process to create a unified voice that is the challenge.

In terms of the pressures of the photography market, I think I’ve largely eschewed the idea of puritanical restraint that I see so many photographers participate in. What I mean by this is a very deliberate elusiveness and practiced in person/online decorum to project this sense of ‘success’ and ‘power.’ It’s reflected in the work, too. I’m an artist because I want to share what I think and feel and how I perceive the world. I’m not a hedge fund manager looking for everyone’s Achilles’ heel. I’m not trying to say that I’m GG Allin or anything, I just think there’s a lot more room for people with a sense of humor. What we’re all doing is pretty ridiculous and seen as both trivial and incomprehensible to the vast majority of people, and the part that I find funny is that they’re partially right. But when we’re right, it’s truer than anything else.

Nich We were commiserating about the 2016 election and you brought up feeling self-conscious about how dark your work is. I wonder how you’re reading it differently, and how you think it will be received differently, under the light of the current political and social moment?

Rory I think I touched a bit upon this in that last paragraph up there. The part I didn’t mention is that I’m not immune to all pressures of being a “professional artist” and the work I’ve been making for the past 3-4 years has veered towards a decidedly darker tone. While I think it’s my strongest work to date, I have had moments of self-consciousness due to the content and how heavy it is. There is a lot of rage in the work, but rage is what got me started on the project in the first place. Obviously, this is a strong emotion, one that is short lived and often results in some embarrassment after it’s passed. In my personal life, the rage subsided so it sidetracked me in finishing up the project and also showing it to others. The election and resultant shitstorm it has brewed has not only reinvigorated my rage but also a collective rage among anyone with a level head. This has made me feel sure that now is the time to let the work see the light of day and I’m glad it’s taken me until now to feel ready.

There is one image of an older white man completely naked with his legs spread open, leaning back on the concrete surrounded by overgrown grass and daisies. I actually kept this in negative form and printed it on transparency film until recently. The positive image—the actual image—of it just felt too much even for me, but right now it’s exactly what we need to be seeing.

In terms of the pressures of the photography market, I think I’ve largely eschewed the idea of puritanical restraint that I see so many photographers participate in. What I mean by this is a very deliberate elusiveness and practiced in person/online decorum to project this sense of ‘success’ and ‘power.’ It’s reflected in the work, too. I’m an artist because I want to share what I think and feel and how I perceive the world. I’m not a hedge fund manager looking for everyone’s Achilles’ heel. I’m not trying to say that I’m GG Allin or anything, I just think there’s a lot more room for people with a sense of humor. What we’re all doing is pretty ridiculous and seen as both trivial and incomprehensible to the vast majority of people, and the part that I find funny is that they’re partially right. But when we’re right, it’s truer than anything else.

Nich We were commiserating about the 2016 election and you brought up feeling self-conscious about how dark your work is. I wonder how you’re reading it differently, and how you think it will be received differently, under the light of the current political and social moment?

Rory I think I touched a bit upon this in that last paragraph up there. The part I didn’t mention is that I’m not immune to all pressures of being a “professional artist” and the work I’ve been making for the past 3-4 years has veered towards a decidedly darker tone. While I think it’s my strongest work to date, I have had moments of self-consciousness due to the content and how heavy it is. There is a lot of rage in the work, but rage is what got me started on the project in the first place. Obviously, this is a strong emotion, one that is short lived and often results in some embarrassment after it’s passed. In my personal life, the rage subsided so it sidetracked me in finishing up the project and also showing it to others. The election and resultant shitstorm it has brewed has not only reinvigorated my rage but also a collective rage among anyone with a level head. This has made me feel sure that now is the time to let the work see the light of day and I’m glad it’s taken me until now to feel ready.

There is one image of an older white man completely naked with his legs spread open, leaning back on the concrete surrounded by overgrown grass and daisies. I actually kept this in negative form and printed it on transparency film until recently. The positive image—the actual image—of it just felt too much even for me, but right now it’s exactly what we need to be seeing.