WHO CAN REPRESENT WHO?

MAMA

David Kasnic interviews pastor Martha Freeman of Alpha & Omega

David Kasnic, Antoine, looking out onto 27th Street, 2016

David Kasnic Can you talk about your church and the neighborhood in which it resides?

Martha Freeman You really don’t have to tell their story. They tell it themselves, and to me that makes it more authentic because it's not like you’re making it up. When CBS came to do a story here, people laughed about this 77-year-old lady walking through the neighborhood, but it happens. That’s actually what I do. I chase them off the corners by saying, “Get out of there. Why hang out there? Why go to jail? Some of you have warrants. Some of you know you have something on you that you shouldn’t have.” I always take them into church because I think that this church is not the typical or the traditional kind of church. We talk about life, and life as it relates to the bible, as it relates to the scriptures telling you how to get through those roadblocks, those habits, those behaviors that would cause you to do life in prison or twenty, thirty years. Just that brief interference gives me the chance to talk to them. Then they’re interested in coming in and sitting down and talking to me. Once they’re comfortable talking about life, they’re comfortable listening to what I have to say in relation to God. So I try to think about it in that way so that I don’t get tired or weary or disgusted when they don’t show up. I just find another way to get them to come. It’s like the donuts (points to free boxes of donuts the church gives out, which are donated by various organizations throughout Milwaukee). That’s a door opener. And I’m not discouraged, because the bible says that you plant a seed. When you plant it, you don’t stand there and watch it grow and develop. You plant it, you go on your way, and it grows. It sprouts. It grows.

So it is with the word of God. So it is with simple words like, “Come to church.” I feel like the Holy Spirit directs those little phrases or those little words and I pray for them (individuals that come into her church) and sometimes I don’t even know their name. Afterwards I pray, and eventually I see them walk in here and that takes away the discouragement. I believe. That’s why I sit here. I don’t expect it to always make sense to my family or other people. My sons were worried. My son Duane was like, “Why do you sit here? Something could happen.” But they don’t understand that my orders come from God. That’s what a church is. It’s a refuge for lost people. You know what I’m saying? So my sitting here is not only good for them. It’s good for me. It keeps me alive, thinking, and moving. Most of all, I’m loving people because what happened to me could make someone real bitter; I choose love over bitterness. I did a good deed for someone and it cost me a son (one of Martha’s sons is currently on trial in Louisiana for a crime she feels he did not commit). I could feel myself getting bitter. But I had to forgive. I really did. This church gave me a reason and purpose to keep on—keep believing—sharing. And I have no doubt in my mind that one of these days my son is going to walk out here, and it’ll be a message to all of them that hope is real; faith is real. That’s what is behind it all. That is what is behind the bread, the church, my sitting here. That’s the whole story in a nutshell, really.

Before then—before that happened with my son—I was given that house over there on North 26th Street. And that started in me a desire to really show love in this neighborhood because that was such a gift. And I wasn’t even really going to church a lot then. I went, but not like I am now. I was on welfare. I had five children and an alcoholic husband. Then, just to get a home, my own home… My son Kevin was just a baby, two years old. You can see the love he has for the neighborhood that he grew up in. He’s got a house upstairs, and he just will not leave this area. He has precious memories from it, and that was the one thing that made me give up myself to the neighborhood. I was so happy to have that house. I thought it was just rich. Nice green grass, apple tree in the backyard, you know? I bought a swimming pool. I bought a swing set. All the kids in the neighborhood came to our yard. It was like fun land. That made me happy, because we were basically poor. We didn’t really have anything. And we graduated to the park (Martha started having neighborhood events in Atkinson Park across the street). I used to have talent shows up there—used my house for the runway. We had sack races, that kind of thing. Just involving the whole neighborhood, and that’s the kind of stuff that I did, but it amazed me that some thirty, forty years later, people started noticing what I’ve been doing for all those years (three weeks after this interview the city of Milwaukee renamed a street in the neighborhood after Martha). And I think a lot of it had to do with Shawn (community leader with Project Make A Change in Milwaukee who brought me to Alpha & Omega). There were times when you could find ten, eleven young people rolled up in blankets because their parents weren’t home. They either were out using drugs, in jail, or whatever. My kids had a habit of bringing home all the runaways. But I guess I never even thought about the impact.

Martha Freeman You really don’t have to tell their story. They tell it themselves, and to me that makes it more authentic because it's not like you’re making it up. When CBS came to do a story here, people laughed about this 77-year-old lady walking through the neighborhood, but it happens. That’s actually what I do. I chase them off the corners by saying, “Get out of there. Why hang out there? Why go to jail? Some of you have warrants. Some of you know you have something on you that you shouldn’t have.” I always take them into church because I think that this church is not the typical or the traditional kind of church. We talk about life, and life as it relates to the bible, as it relates to the scriptures telling you how to get through those roadblocks, those habits, those behaviors that would cause you to do life in prison or twenty, thirty years. Just that brief interference gives me the chance to talk to them. Then they’re interested in coming in and sitting down and talking to me. Once they’re comfortable talking about life, they’re comfortable listening to what I have to say in relation to God. So I try to think about it in that way so that I don’t get tired or weary or disgusted when they don’t show up. I just find another way to get them to come. It’s like the donuts (points to free boxes of donuts the church gives out, which are donated by various organizations throughout Milwaukee). That’s a door opener. And I’m not discouraged, because the bible says that you plant a seed. When you plant it, you don’t stand there and watch it grow and develop. You plant it, you go on your way, and it grows. It sprouts. It grows.

So it is with the word of God. So it is with simple words like, “Come to church.” I feel like the Holy Spirit directs those little phrases or those little words and I pray for them (individuals that come into her church) and sometimes I don’t even know their name. Afterwards I pray, and eventually I see them walk in here and that takes away the discouragement. I believe. That’s why I sit here. I don’t expect it to always make sense to my family or other people. My sons were worried. My son Duane was like, “Why do you sit here? Something could happen.” But they don’t understand that my orders come from God. That’s what a church is. It’s a refuge for lost people. You know what I’m saying? So my sitting here is not only good for them. It’s good for me. It keeps me alive, thinking, and moving. Most of all, I’m loving people because what happened to me could make someone real bitter; I choose love over bitterness. I did a good deed for someone and it cost me a son (one of Martha’s sons is currently on trial in Louisiana for a crime she feels he did not commit). I could feel myself getting bitter. But I had to forgive. I really did. This church gave me a reason and purpose to keep on—keep believing—sharing. And I have no doubt in my mind that one of these days my son is going to walk out here, and it’ll be a message to all of them that hope is real; faith is real. That’s what is behind it all. That is what is behind the bread, the church, my sitting here. That’s the whole story in a nutshell, really.

Before then—before that happened with my son—I was given that house over there on North 26th Street. And that started in me a desire to really show love in this neighborhood because that was such a gift. And I wasn’t even really going to church a lot then. I went, but not like I am now. I was on welfare. I had five children and an alcoholic husband. Then, just to get a home, my own home… My son Kevin was just a baby, two years old. You can see the love he has for the neighborhood that he grew up in. He’s got a house upstairs, and he just will not leave this area. He has precious memories from it, and that was the one thing that made me give up myself to the neighborhood. I was so happy to have that house. I thought it was just rich. Nice green grass, apple tree in the backyard, you know? I bought a swimming pool. I bought a swing set. All the kids in the neighborhood came to our yard. It was like fun land. That made me happy, because we were basically poor. We didn’t really have anything. And we graduated to the park (Martha started having neighborhood events in Atkinson Park across the street). I used to have talent shows up there—used my house for the runway. We had sack races, that kind of thing. Just involving the whole neighborhood, and that’s the kind of stuff that I did, but it amazed me that some thirty, forty years later, people started noticing what I’ve been doing for all those years (three weeks after this interview the city of Milwaukee renamed a street in the neighborhood after Martha). And I think a lot of it had to do with Shawn (community leader with Project Make A Change in Milwaukee who brought me to Alpha & Omega). There were times when you could find ten, eleven young people rolled up in blankets because their parents weren’t home. They either were out using drugs, in jail, or whatever. My kids had a habit of bringing home all the runaways. But I guess I never even thought about the impact.

David Kasnic (from top), Israel, looking into Alpha & Omega, 2017;

Mom & Daughter, after a morning service on 27th Street, 2017; Johnny Steel, 2016

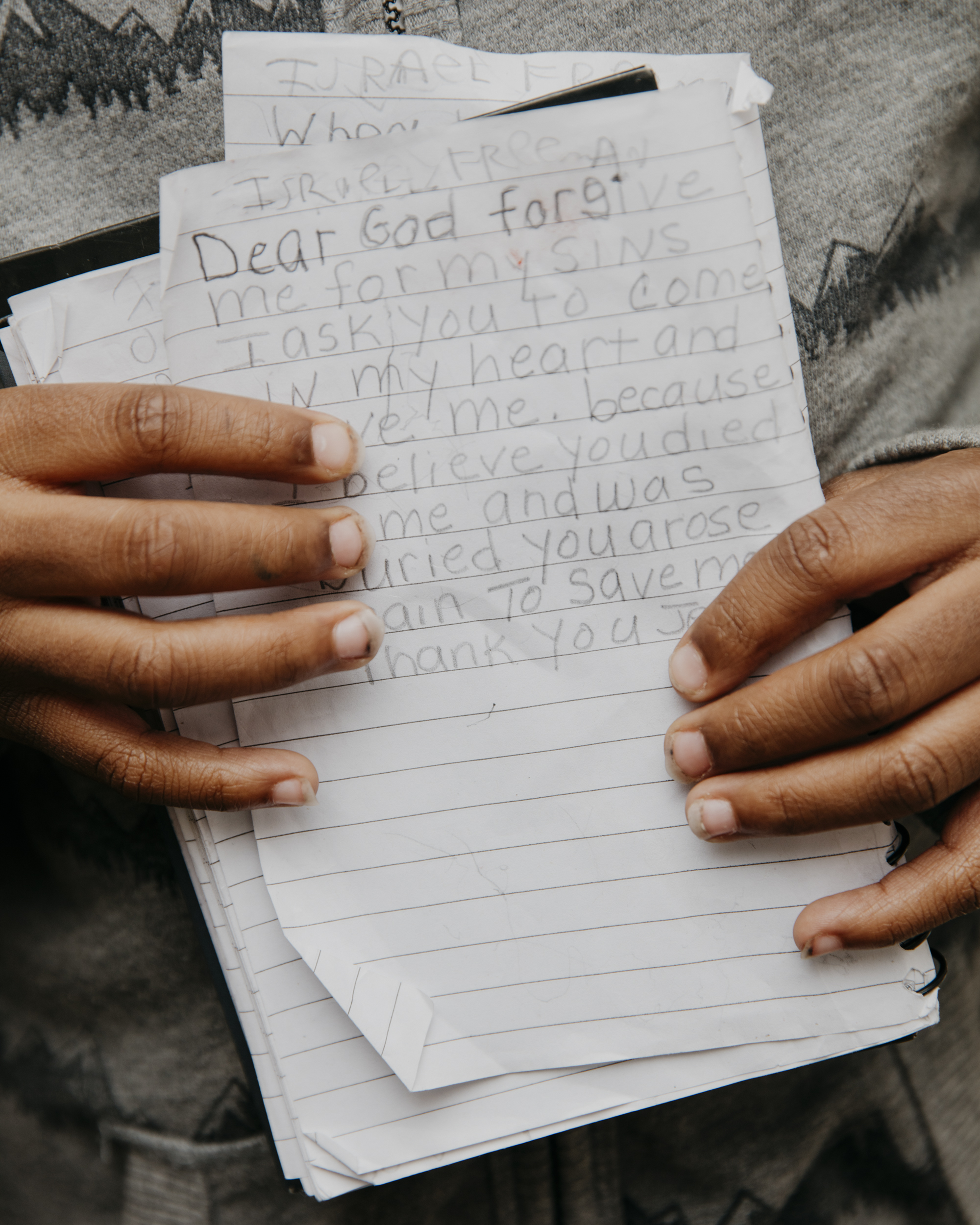

David Kasnic, Israel's noteboo, 2016

David Kasnic, Israel's noteboo, 2016

David I want to ask you about our initial meeting. What was it like for Shawn, a community leader with Project Make A Change in Milwaukee, to bring two white men, one from France, to your church on that Sunday in September?

Martha I welcomed you coming. I think what I had a problem with was, why me? What is it about me? I guess more and more I’m beginning to realize the impact that my life had on Shawn’s life. All the years that he grew up around me I didn’t realize that I had such an impact. That was the only question I had when you first came. Why me? You know, what was I doing that was so different? No one ever gave me that much attention.

David How did you feel when I kept coming back?

Martha That to me was the… how can I say it? That was the most beautiful part of that whole thing, you know, with you and the reporter coming, that you kept coming and, honestly, I don’t think you knew why you kept coming. I really don’t. Because I could see that it was more, something more than just photography. You know? And the way that my family and the church members took to you, even people in the community, even though they questioned at first your being here. I think it was good that they trusted me, because then they began to be comfortable with you. And I thought that was the most beautiful part of it, how God had put the two of us together. It still amazes me that you keep coming. But I guess I just feel like it’s not all work and it’s not all about photography. I just think that it’s people getting to know one another and developing a relationship outside of church, outside of me being a pastor and you being a photographer.

Martha I welcomed you coming. I think what I had a problem with was, why me? What is it about me? I guess more and more I’m beginning to realize the impact that my life had on Shawn’s life. All the years that he grew up around me I didn’t realize that I had such an impact. That was the only question I had when you first came. Why me? You know, what was I doing that was so different? No one ever gave me that much attention.

David How did you feel when I kept coming back?

Martha That to me was the… how can I say it? That was the most beautiful part of that whole thing, you know, with you and the reporter coming, that you kept coming and, honestly, I don’t think you knew why you kept coming. I really don’t. Because I could see that it was more, something more than just photography. You know? And the way that my family and the church members took to you, even people in the community, even though they questioned at first your being here. I think it was good that they trusted me, because then they began to be comfortable with you. And I thought that was the most beautiful part of it, how God had put the two of us together. It still amazes me that you keep coming. But I guess I just feel like it’s not all work and it’s not all about photography. I just think that it’s people getting to know one another and developing a relationship outside of church, outside of me being a pastor and you being a photographer.

David Kasnic, Deacon's hand, 2017

David

Can you talk about how the neighborhood has changed since you first moved here in the 1960s?

Martha Did I show you the house that we lived in? Our house was the only house on that block that had a Black family in 1969. On the other side of the street it was totally white. At six o’clock in the evening it was totally quiet. Nobody was moving around other than just sitting on their porches or whatever. You didn’t hear gunshots. You didn’t see gangs of people walking up and down the sidewalk. You didn’t see that. There were stores—like I said, a drug store, Dutchland Dairy, which was like the Dairy Queen stores. They sold ice cream and hamburgers and that kind of stuff. It was a real huge, big store. I could show it to you. It was like halfway—no, wait, they tore it down. They turned it into a church. But it was like a large restaurant. I think I noticed the shift in about the early ’80s. In the ’60s and ’70s it was still like that kind of neighborhood. I was teaching school then and going to UWM (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee), but around the ’80s was when a lot of stuff started—a lot of crimes. I went to corrections in 1995, and I had been working as a private detective in the ’80s for a defense attorney. I started out working for her because my kids got in trouble.

David How do you feel that a church like yours is important?

Martha Did I show you the house that we lived in? Our house was the only house on that block that had a Black family in 1969. On the other side of the street it was totally white. At six o’clock in the evening it was totally quiet. Nobody was moving around other than just sitting on their porches or whatever. You didn’t hear gunshots. You didn’t see gangs of people walking up and down the sidewalk. You didn’t see that. There were stores—like I said, a drug store, Dutchland Dairy, which was like the Dairy Queen stores. They sold ice cream and hamburgers and that kind of stuff. It was a real huge, big store. I could show it to you. It was like halfway—no, wait, they tore it down. They turned it into a church. But it was like a large restaurant. I think I noticed the shift in about the early ’80s. In the ’60s and ’70s it was still like that kind of neighborhood. I was teaching school then and going to UWM (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee), but around the ’80s was when a lot of stuff started—a lot of crimes. I went to corrections in 1995, and I had been working as a private detective in the ’80s for a defense attorney. I started out working for her because my kids got in trouble.

David How do you feel that a church like yours is important?

David Kasnic, Israel, in front of the free bread

Martha You know what, Dave? At the risk of sounding like I’m all it, there’s a church on the corner. There’s a huge church down the street a ways and another one this way. And they just do a lot of singing, a lot of everything except reaching the lives, you know what I’m saying? Over here (points to a church across the street) there’s people that come from the south side and say that they want to evangelize over here because this is one of the worst areas in Milwaukee, but if you were here, if they were here everyday—you know, when I’m here, you don’t see fighting out there. You have to put the work in, the heart in. These are the kind of people that need to have a relationship of trust.

David Someone like myself, I can come here as much as possible, interact as much as possible, but at the end of the day I’ll always be an outsider here.

Martha There’s your answer. You answered your own question, really. Because you once said you could never know what it’s like to be a Black man in America. He can never know what it’s like to be you. I guess, to me, should that stop people from interacting with one another? We flip the coin to my son Kevin. Okay, even though Kevin is of African American descent his experience as a little guy growing up in this neighborhood was different. And it was different because I wanted something different for all my kids and, if ever I wanted an accolade for anything, it would be for that. You know? Like I said, my husband was an alcoholic. He was the most beautiful person when he wasn’t drinking. When he was drinking, he was a monster. I wear dentures because of that. You know, he would just come home, I remember, on my knees scrubbing the floor, because we didn’t always have a mop, but my house was spotless, and he just came in and he was like, “What are you doing down there on your knees?” And he just hit me. I had to have all of my teeth removed because he damaged my face. I used to try not to fight with him, even though I felt like I could, until eventually I got tired of it and I just showed him that I could really beat him if I wanted to. So, by the time I got through beating him up, it was over.

Martha There’s your answer. You answered your own question, really. Because you once said you could never know what it’s like to be a Black man in America. He can never know what it’s like to be you. I guess, to me, should that stop people from interacting with one another? We flip the coin to my son Kevin. Okay, even though Kevin is of African American descent his experience as a little guy growing up in this neighborhood was different. And it was different because I wanted something different for all my kids and, if ever I wanted an accolade for anything, it would be for that. You know? Like I said, my husband was an alcoholic. He was the most beautiful person when he wasn’t drinking. When he was drinking, he was a monster. I wear dentures because of that. You know, he would just come home, I remember, on my knees scrubbing the floor, because we didn’t always have a mop, but my house was spotless, and he just came in and he was like, “What are you doing down there on your knees?” And he just hit me. I had to have all of my teeth removed because he damaged my face. I used to try not to fight with him, even though I felt like I could, until eventually I got tired of it and I just showed him that I could really beat him if I wanted to. So, by the time I got through beating him up, it was over.

David I guess what I’m really trying to ask is how do you feel about a white man coming into your church and your community? Who can represent who?

Martha I felt honored. Well, I guess I’m not as unnerved about it as somebody else would probably be. And I think that’s mainly because of my work in corrections (Wisconsin Department of Corrections), where you work with all races. You know, in corrections you have to look past the race kind of thing, because you have to work so closely together and you’re expected to complement one another and protect one another, so you kind of lose the racial thing. The way you look at a person, somehow that goes away. The more you came every week, and the more we talked and shared things, I became comfortable with your being here and with sharing different stories with you, sharing what I thought about the church, about the community. I think it was more uncomfortable for the people in the community than it was for me because initially they thought you were a suspect cop or that you were undercover because of the kind of crimes and things that go on in this neighborhood and it’s a predominately Black neighborhood. They all know that I worked in corrections, so a lot of them felt like you were undercover for awhile until they really saw you coming every week, and I think they became real comfortable with you being around. I could tell that because you weren’t harassed. If they suspected that there was something undercover about you, they would have harassed you, they would have made it difficult for you, but anytime they see you coming here or see me talking to you or anyone else, they sort of protect. It’s like ladies, even the females that walk up and down the street, if they stop here, that's the end of the harassment. I don’t know how to say it any other way other than respect, and I think that even though some of the individuals in this neighborhood may be criminals, they might even be on the run, or just gotten out of the house of corrections, just released, there is a certain kind of respect here, and I think it’s because I respect them too, regardless of what they’re into. I think that has taken a lot of the fear a person would have, like me here in this place by myself early in the morning, late at night, middle of the day. I’m here, you know. If I drive up with a load of food, by the time I look around it’s all set out (Martha gathers donated loaves of bread, buns and other food in car loads, and sets them outside of her church for free). So I guess to really get back to your question, I think that the neighborhood has accepted you as I have and certainly my family.

Martha I felt honored. Well, I guess I’m not as unnerved about it as somebody else would probably be. And I think that’s mainly because of my work in corrections (Wisconsin Department of Corrections), where you work with all races. You know, in corrections you have to look past the race kind of thing, because you have to work so closely together and you’re expected to complement one another and protect one another, so you kind of lose the racial thing. The way you look at a person, somehow that goes away. The more you came every week, and the more we talked and shared things, I became comfortable with your being here and with sharing different stories with you, sharing what I thought about the church, about the community. I think it was more uncomfortable for the people in the community than it was for me because initially they thought you were a suspect cop or that you were undercover because of the kind of crimes and things that go on in this neighborhood and it’s a predominately Black neighborhood. They all know that I worked in corrections, so a lot of them felt like you were undercover for awhile until they really saw you coming every week, and I think they became real comfortable with you being around. I could tell that because you weren’t harassed. If they suspected that there was something undercover about you, they would have harassed you, they would have made it difficult for you, but anytime they see you coming here or see me talking to you or anyone else, they sort of protect. It’s like ladies, even the females that walk up and down the street, if they stop here, that's the end of the harassment. I don’t know how to say it any other way other than respect, and I think that even though some of the individuals in this neighborhood may be criminals, they might even be on the run, or just gotten out of the house of corrections, just released, there is a certain kind of respect here, and I think it’s because I respect them too, regardless of what they’re into. I think that has taken a lot of the fear a person would have, like me here in this place by myself early in the morning, late at night, middle of the day. I’m here, you know. If I drive up with a load of food, by the time I look around it’s all set out (Martha gathers donated loaves of bread, buns and other food in car loads, and sets them outside of her church for free). So I guess to really get back to your question, I think that the neighborhood has accepted you as I have and certainly my family.

David Kasnic, Cheek kiss, 2016

David Your church is one of the only female run churches in Milwaukee.

Martha A lot of times in the Black community females don’t get the respect that they should get. And a lot of it is because many people, they go to church, they sit here, and they hear, but they don’t read. They hear somebody else's perspective or how somebody else interprets the scripture and so a lot of people are taught that females should not preach. They should not do what’s called “usurp” authority over men. That means that we shouldn’t be in charge, but that isn’t what that scripture was all about. Back in those days women would go to church and they would really make a mockery of their husbands by asking questions and speaking out and acting like they knew it all. Paul said that for this reason women needed to be quiet in the church, but when you read Joel Chapter 2, I think it’s about verse 26, it says that God will pour out his spirit on all flesh, male and female, and that they will prophesy. And when you read it, you read about Deborah. She was a prophet. You read about Aquila and Priscilla. And I guess I’m saying that if you say you’re going to do God’s work, you have to look past what other people say. I’m going to do a series on that one Sunday—about approval addiction. A lot of people are addicted to somebody else's approval of them. I grew past that. In fact, I was very familiar with being told that I was nothing, never going to be nothing, and my way of dealing with that was “I’ll show you.” I came into this church, I believe, being very humble and innocent. I came in here because I started to work third shift as a sergeant. And my family was going through something at a different church and we all started to drift away and go to other churches, so I started to call meetings to find out what was wrong, what can we do about it, in the hopes of not separating.

Martha A lot of times in the Black community females don’t get the respect that they should get. And a lot of it is because many people, they go to church, they sit here, and they hear, but they don’t read. They hear somebody else's perspective or how somebody else interprets the scripture and so a lot of people are taught that females should not preach. They should not do what’s called “usurp” authority over men. That means that we shouldn’t be in charge, but that isn’t what that scripture was all about. Back in those days women would go to church and they would really make a mockery of their husbands by asking questions and speaking out and acting like they knew it all. Paul said that for this reason women needed to be quiet in the church, but when you read Joel Chapter 2, I think it’s about verse 26, it says that God will pour out his spirit on all flesh, male and female, and that they will prophesy. And when you read it, you read about Deborah. She was a prophet. You read about Aquila and Priscilla. And I guess I’m saying that if you say you’re going to do God’s work, you have to look past what other people say. I’m going to do a series on that one Sunday—about approval addiction. A lot of people are addicted to somebody else's approval of them. I grew past that. In fact, I was very familiar with being told that I was nothing, never going to be nothing, and my way of dealing with that was “I’ll show you.” I came into this church, I believe, being very humble and innocent. I came in here because I started to work third shift as a sergeant. And my family was going through something at a different church and we all started to drift away and go to other churches, so I started to call meetings to find out what was wrong, what can we do about it, in the hopes of not separating.

The meetings led into my being here. I’d already been ordained as an evangelist, so it wasn’t difficult to start bringing the message. One night the old pastor called me and he said, “I haven’t slept all night. God told me that I need to ordain you as pastor.” And I said, “For real?” And he said, “Yes.” He said, “I could see you standing in front of a crowd of people.” I said, “Okay.” So, that’s how I really just settled in this place, but the thought was not to start a church. I remember distinctly one Easter Sunday he was preaching the message and I know everybody was just sitting there. He was talking about how Jesus just died but saved everyone and that his mother was there watching the whole thing. So, I raised my hand and…God, I didn’t even know you don’t talk while somebody’s delivering the message, but I raised my hand and said, “I wouldn’t have done that. To let my son die for people who didn’t appreciate him. I wouldn’t have sat there and watched that.” He just shook his head and he said, “Most people are thinking what you dared to say.” Afterwards he said that comment needed to be made. When he died his wife gave me everything. I just learned so much from him, and it’s really something, how it all happened. He used to say, “This has got to be a church on this corner. It must be.” I guess it was meant for me. It’s really something. This was in 1970.

David Kasnic, Martha, outside of Alpha & Omega on 27th Street handing out bread, 2017

David I can relate to your comment about being addicted to approval, especially with photography.

Martha I think if you put aside even looking for a hint of appreciation or approval and base everything on what you do, on what you feel, the relationship you’ve formed with me, and what you’ve learned from being around, I think they’ll be amazed. You know, just envious. I would always say to my kids, “Don’t ever let anybody white make you hold your head down. If the police stop you, you hold your head up. You talk. You speak. You don’t look down. You look up.” It was always this fighting stance, that’s the way my kids grew up. That approval thing is really something. It all goes back to me teaching my kids not to fish for approval. Know yourself. Know what you want to do. That’s the only way that I got up out of the slump that I was in. When I finally got enough nerve to get a divorce, my husband was like, “If you do this, I’ll kill you.” I said, “Well, you better start doing it right now, because I’m out of here.” I had just had enough. I felt like I was not even a human being. Once I got a divorce, he said to me, “I’ll bet you it won’t be long before they kick you out of this house.” And I’m like, “How can you even say that? I pay the bills. I work three jobs. I pay for this. I go clean houses, night and day.” And I never was out of the house. I never lost the house. But I worked like a dog, and then it finally got to the point where I couldn’t even have a boyfriend because I didn’t want anybody over my kids. I didn’t want that. It all ties into that approval. You just know yourself and—if you know yourself—don’t worry about what other people think, but that’s hard.

Martha I think if you put aside even looking for a hint of appreciation or approval and base everything on what you do, on what you feel, the relationship you’ve formed with me, and what you’ve learned from being around, I think they’ll be amazed. You know, just envious. I would always say to my kids, “Don’t ever let anybody white make you hold your head down. If the police stop you, you hold your head up. You talk. You speak. You don’t look down. You look up.” It was always this fighting stance, that’s the way my kids grew up. That approval thing is really something. It all goes back to me teaching my kids not to fish for approval. Know yourself. Know what you want to do. That’s the only way that I got up out of the slump that I was in. When I finally got enough nerve to get a divorce, my husband was like, “If you do this, I’ll kill you.” I said, “Well, you better start doing it right now, because I’m out of here.” I had just had enough. I felt like I was not even a human being. Once I got a divorce, he said to me, “I’ll bet you it won’t be long before they kick you out of this house.” And I’m like, “How can you even say that? I pay the bills. I work three jobs. I pay for this. I go clean houses, night and day.” And I never was out of the house. I never lost the house. But I worked like a dog, and then it finally got to the point where I couldn’t even have a boyfriend because I didn’t want anybody over my kids. I didn’t want that. It all ties into that approval. You just know yourself and—if you know yourself—don’t worry about what other people think, but that’s hard.

David Kasnic interviews Martha Freeman