HOME

Widline Cadet, Self Portrait in R.'s House, 2016

Patrice Helmar and Widline Cadet were introduced via their mutual friend and photographer, Katie Kline. Katie recommended Widline as a speaker for one of Patrice's curatorial projects, The Marble Hill Camera Club. This conversation takes place after Widline's presentation in February of 2018. Widline and Patrice realized although their work was being made thousands of miles apart, there were connective threads.

Patrice Helmar When did you start making the photographs of home?

Widline Cadet It all started in 2013. I was graduating from undergrad, had no idea what I wanted to do, and didn’t have a solid body of work that I could do anything with. I applied for a fellowship that would let me travel to anywhere outside the U.S. for a year and make pictures. I hadn’t been back to Haiti since I was eleven or so, but after talking with my mom, who had gone back the previous year for the first time in over a decade, my interest in my family and in Haiti grew. I wanted to know more about both and that’s where the project came from.

Patrice I came here as 31-year-old and I was freaked out so I can’t imagine. You were going into middle school.

Widline Yeah, that was 6th grade. So it was an experience for sure, and I didn’t speak much English the entire year that I was in 6th grade. You get thrown into these things, and you learn your way through. I was living in Washington Heights. My older siblings were in Crown Heights, which had a huge Haitian population and I would also spend time there. But in Washington Heights it’s a completely different territory.

How was your first experience living away from home—out of Alaska?

Patrice Well it was my first time living “down south”—as Alaskans we call everything below us down south—and that refers to anything from Australia, Japan, etc. I was from such a small town. I went to school in Oregon right out of high school. I was so homesick. It seemed like such a huge place even though it was just another small town. I just really wanted to come home. I remember calling home so much the first month that my parents were like, “don’t call us anymore.”

Widline Cadet It all started in 2013. I was graduating from undergrad, had no idea what I wanted to do, and didn’t have a solid body of work that I could do anything with. I applied for a fellowship that would let me travel to anywhere outside the U.S. for a year and make pictures. I hadn’t been back to Haiti since I was eleven or so, but after talking with my mom, who had gone back the previous year for the first time in over a decade, my interest in my family and in Haiti grew. I wanted to know more about both and that’s where the project came from.

Patrice I came here as 31-year-old and I was freaked out so I can’t imagine. You were going into middle school.

Widline Yeah, that was 6th grade. So it was an experience for sure, and I didn’t speak much English the entire year that I was in 6th grade. You get thrown into these things, and you learn your way through. I was living in Washington Heights. My older siblings were in Crown Heights, which had a huge Haitian population and I would also spend time there. But in Washington Heights it’s a completely different territory.

How was your first experience living away from home—out of Alaska?

Patrice Well it was my first time living “down south”—as Alaskans we call everything below us down south—and that refers to anything from Australia, Japan, etc. I was from such a small town. I went to school in Oregon right out of high school. I was so homesick. It seemed like such a huge place even though it was just another small town. I just really wanted to come home. I remember calling home so much the first month that my parents were like, “don’t call us anymore.”

Patrice Helmar, Aurora Harbor, 2015

Widline & Patrice [laugh]

Patrice They said, “Go make some friends. Talk to people—it’s not that bad you know.”

Widline Unbelievable!

Patrice Right, but it was really expensive. Long distance in the early 2000s. It was hard to call home. What about you? Was there a way for you to stay in touch with your friends back in Haiti when you got [to New York]?

Widline Cadet, V. in Pool, 2016; Lot, 2016

Widline At first a little and then not at all. That’s the thing. I completely lost touch with my friends in Haiti, I wasn’t acclimating as well to making new friends, and I became pretty withdrawn. I felt very secluded in my space, but it wasn’t even my space to begin with. But after that I got better… I knew the language and how to act. When you realize how to act in certain spaces a lot of things change.

With my siblings, even though we’re the same generation, we’ve had very different experiences both in Haiti and America, and I think that’s something that’s dependent on how old they were when they immigrated. I’m the youngest out of everyone that was born in Haiti and compared to them I’ve had a life of luxury. They were older, had more of an attachment to Haiti, and had far less time for self actualization here. And that’s why I refer to my making art as an an indulgence.

Patrice But that’s something that’s in both of our work. We’re thinking about what it means. I feel that Alaska is my country if that makes sense. It’s where I’m from.

Widline And do you still feel that way when you go back now?

Patrice I do. I really love New York a lot, too. What about you, how does it feel when you go home to Haiti?

With my siblings, even though we’re the same generation, we’ve had very different experiences both in Haiti and America, and I think that’s something that’s dependent on how old they were when they immigrated. I’m the youngest out of everyone that was born in Haiti and compared to them I’ve had a life of luxury. They were older, had more of an attachment to Haiti, and had far less time for self actualization here. And that’s why I refer to my making art as an an indulgence.

Patrice But that’s something that’s in both of our work. We’re thinking about what it means. I feel that Alaska is my country if that makes sense. It’s where I’m from.

Widline And do you still feel that way when you go back now?

Patrice I do. I really love New York a lot, too. What about you, how does it feel when you go home to Haiti?

Widline I think… it’s home. But I also call New York home. That’s something I’ve been thinking of a lot recently since I moved to Syracuse. When I’m in Syracuse and going to New York, I say I’m going home. When I’m in New York and going to Syracuse, I say I’m going home. When I’m here and going to Haiti, I also refer to it as home. So a lot of my work is trying to find out where that sense of home or place comes from.

Do you think that’s something you’re interested in—in the photos that you’re making?

Patrice Yeah, big time. I always think of this quote by the great writer Carson McCullers. She talks about how Americans are always homesick, but they don’t really know what they’re homesick for.

Widline For sure. Do you think your history with a place plays an important part in a sense of home, or this lack of home?

Patrice It’s evident when I look at your photos, I know you love Haiti and feel connected to it. It comes through in your work. It’s similar to the way that I love Alaska. I’m looking at a couple of pictures where you have figures with the mountains. It’s your way of depicting where you’re from. It’s different from what you watch on the news. Similarly, if you saw a reality show about Alaska, it would look different from my photographs. I was really worried for a long time about making work in Alaska because there are so many ideas about what it is.

Do you think that’s something you’re interested in—in the photos that you’re making?

Patrice Yeah, big time. I always think of this quote by the great writer Carson McCullers. She talks about how Americans are always homesick, but they don’t really know what they’re homesick for.

Widline For sure. Do you think your history with a place plays an important part in a sense of home, or this lack of home?

Patrice It’s evident when I look at your photos, I know you love Haiti and feel connected to it. It comes through in your work. It’s similar to the way that I love Alaska. I’m looking at a couple of pictures where you have figures with the mountains. It’s your way of depicting where you’re from. It’s different from what you watch on the news. Similarly, if you saw a reality show about Alaska, it would look different from my photographs. I was really worried for a long time about making work in Alaska because there are so many ideas about what it is.

Widline And how do you grapple with those ideas which are a lot of times forced on the place that you come from?

Patrice I’d ask you the same question.

Widline Well, I think I should give some background on the project. Originally, as part of the fellowship, I planned on photographing the aftermath of the deadly 2010 earthquake that occured in Haiti. And that wasn’t something that was necessarily going to revolve specifically around my family, but in a more general sense about the Haitian people. When I got there, there was such an apprehension from the people I wanted to photograph, outside of my family…there was such a strong rejection to the idea of being photographed that I had to stop and ask myself if this was really what I wanted or was needed. Was I adding anything new to the conversation?

Patrice I think about this a lot when I’m teaching undergraduate photo. Sometimes our intentions don’t matter. The photograph goes out in the world, and we can’t be there to hold its hand. We are responsible for the photographs that we make.

Widline And to the people that we ask to photograph especially.

Patrice And what’s clear to me in your photographs is that people trust and care for you, and are actively engaged with you while you’re making work. You’re not taking cheap shots.

Patrice I’d ask you the same question.

Widline Well, I think I should give some background on the project. Originally, as part of the fellowship, I planned on photographing the aftermath of the deadly 2010 earthquake that occured in Haiti. And that wasn’t something that was necessarily going to revolve specifically around my family, but in a more general sense about the Haitian people. When I got there, there was such an apprehension from the people I wanted to photograph, outside of my family…there was such a strong rejection to the idea of being photographed that I had to stop and ask myself if this was really what I wanted or was needed. Was I adding anything new to the conversation?

Patrice I think about this a lot when I’m teaching undergraduate photo. Sometimes our intentions don’t matter. The photograph goes out in the world, and we can’t be there to hold its hand. We are responsible for the photographs that we make.

Widline And to the people that we ask to photograph especially.

Patrice And what’s clear to me in your photographs is that people trust and care for you, and are actively engaged with you while you’re making work. You’re not taking cheap shots.

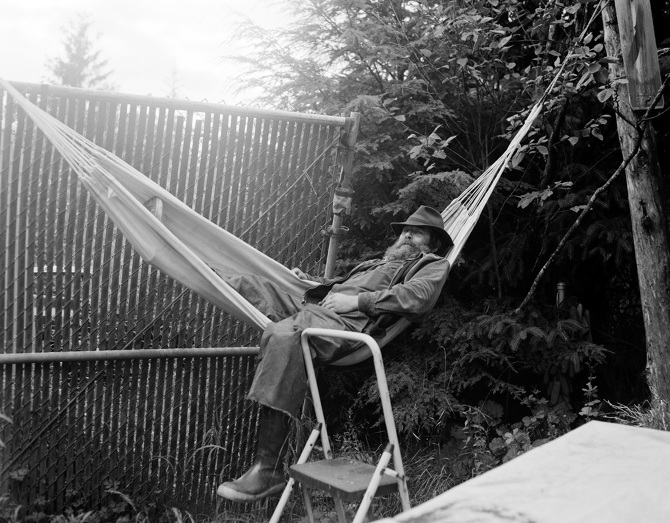

Patrice Helmar, Nellie at the Arctic, 2016; Tattoo in His Hammock, 2016

Widline That got me wondering, how well do you know all the people you photograph?

Patrice Sometimes tourists or summer workers visiting Alaska creep into my work. I love the Jack London costumes they wear, but generally my photographs are friends, family, or kids I know but I don't know. Or this guy I’ve seen around town for like 20 years. And what about with you? Are most of the people in the photographs your relatives?

Widline Yeah, they are all of my relatives. Some of them I knew before I left Haiti, and others that I’d never met. My sisters and their children show up in the work a lot as well.

Patrice I want to ask you about this one photograph [M. Eight Months Pregnant]. It has to be one of the strongest photographs I’ve ever seen of a pregnant woman. And I’m wondering if you could talk about making that photo.

Widline It’s one of my older sisters. She lives in the South. She was pregnant at the time (clearly) and I had been waiting for years for her to give me a niece or a nephew. So when it finally happened, I told her that this was the one time I was going to use my photography skills for something useful.

Widline & Patrice [laugh]

Patrice Was she happy with the photo?

Patrice Sometimes tourists or summer workers visiting Alaska creep into my work. I love the Jack London costumes they wear, but generally my photographs are friends, family, or kids I know but I don't know. Or this guy I’ve seen around town for like 20 years. And what about with you? Are most of the people in the photographs your relatives?

Widline Yeah, they are all of my relatives. Some of them I knew before I left Haiti, and others that I’d never met. My sisters and their children show up in the work a lot as well.

Patrice I want to ask you about this one photograph [M. Eight Months Pregnant]. It has to be one of the strongest photographs I’ve ever seen of a pregnant woman. And I’m wondering if you could talk about making that photo.

Widline It’s one of my older sisters. She lives in the South. She was pregnant at the time (clearly) and I had been waiting for years for her to give me a niece or a nephew. So when it finally happened, I told her that this was the one time I was going to use my photography skills for something useful.

Widline & Patrice [laugh]

Patrice Was she happy with the photo?

Widline I think so. That’s the thing I sometimes have to negotiate with my family. I make pictures for them, and then I make pictures for me. The one that you saw was more for me to be honest…

Patrice You have so much in the photograph. The look on her face is not serene, but she knows what she’s doing. It’s just a very empowered beautiful photograph. It’s different than a lot of pictures you see of women that are pregnant.

Widline Thank you. The funny thing about that image is I always feel like I have to ask her permission before I use it for anything. That’s true for a lot of my pictures as well because my family is not in the public sphere or anything, and they don’t practice art. They’re also very private, so I think in terms of where their images ends up is very important to them and to me. They don’t say it to me, but I think it’s in the back of their mind.

Do the people you photograph ask you where the pictures are going to end up?

Patrice I shoot film. I never know if it’s going to turn out or not. Not to let myself off the hook, but it can be a high rate of failure with large format. Often, I don’t even like the pictures that I take. So I say I don’t know what’s going to happen with these photographs. Hopefully some day they’ll be in a book, hopefully someday I’ll have a show. I tell people I’m an artist—which is a four letter word.

Patrice & Widline [laugh]

Patrice You have so much in the photograph. The look on her face is not serene, but she knows what she’s doing. It’s just a very empowered beautiful photograph. It’s different than a lot of pictures you see of women that are pregnant.

Widline Thank you. The funny thing about that image is I always feel like I have to ask her permission before I use it for anything. That’s true for a lot of my pictures as well because my family is not in the public sphere or anything, and they don’t practice art. They’re also very private, so I think in terms of where their images ends up is very important to them and to me. They don’t say it to me, but I think it’s in the back of their mind.

Do the people you photograph ask you where the pictures are going to end up?

Patrice I shoot film. I never know if it’s going to turn out or not. Not to let myself off the hook, but it can be a high rate of failure with large format. Often, I don’t even like the pictures that I take. So I say I don’t know what’s going to happen with these photographs. Hopefully some day they’ll be in a book, hopefully someday I’ll have a show. I tell people I’m an artist—which is a four letter word.

Patrice & Widline [laugh]

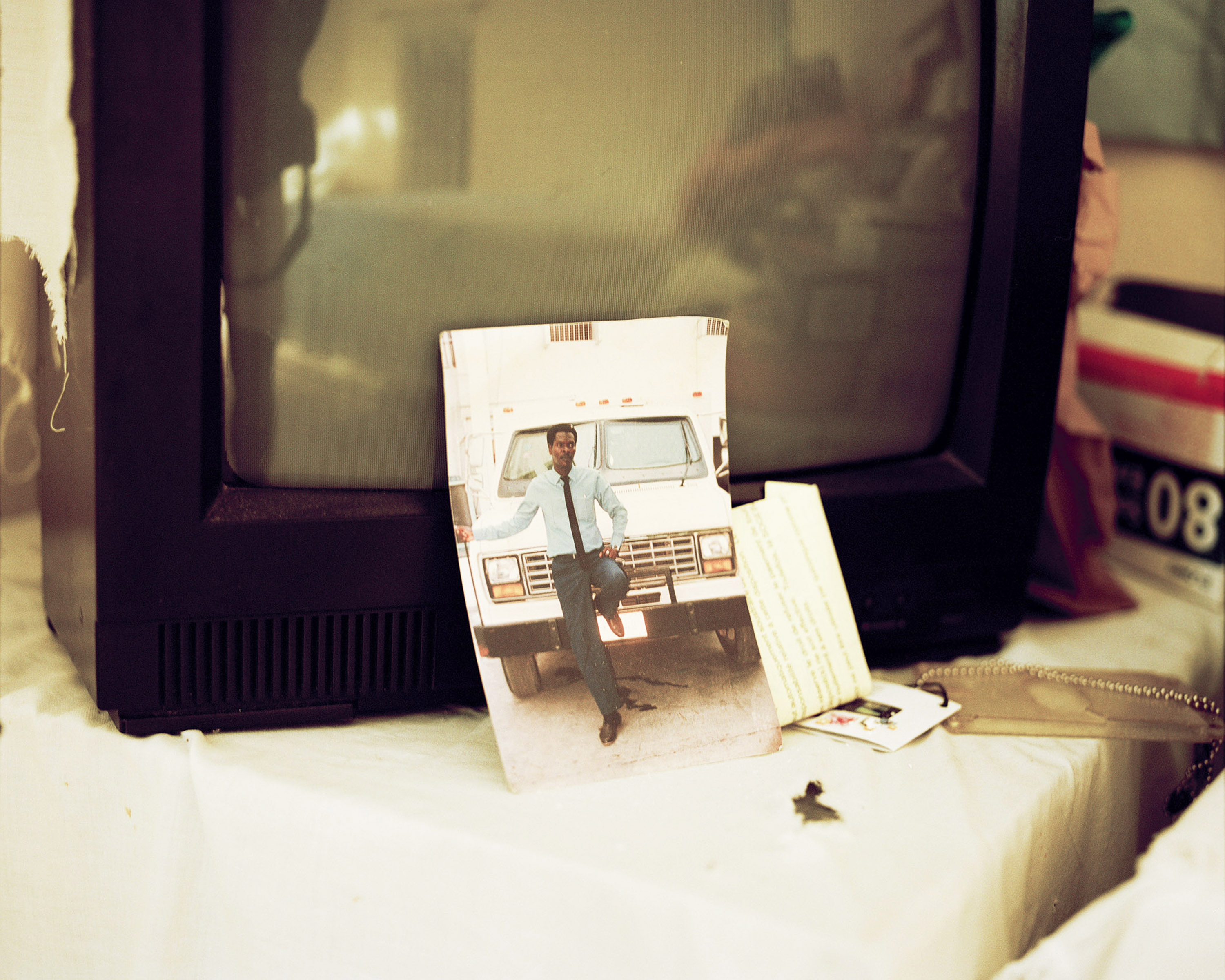

Widline Cadet (clockwise from top), M. Eight Months Pregnant, 2016; Sunset Landscape, 2016; Old Photograph of W., 2013

Patrice Can you tell me about Old Photograph of W.?

Widline That’s actually one of the few photographs I’ve seen of my dad when he was younger. It’s also an example where I think photography has played such an important role in my life because there was such a lack of it. When I went to Haiti at the beginning. I was looking for pictures of my grandparents on my mother’s side, who I never met, and I couldn’t find a single one of them. There are no picture records, and given that it’s a fairly recent generation, I was really heartbroken by that.

Patrice Why do you think there were no pictures?

Widline In my grandma’s case, the fact that she died young is a part of that, but accessibility plays a big role in it as well—at that time, they had no access to the tools to make photographs.

Widline That’s actually one of the few photographs I’ve seen of my dad when he was younger. It’s also an example where I think photography has played such an important role in my life because there was such a lack of it. When I went to Haiti at the beginning. I was looking for pictures of my grandparents on my mother’s side, who I never met, and I couldn’t find a single one of them. There are no picture records, and given that it’s a fairly recent generation, I was really heartbroken by that.

Patrice Why do you think there were no pictures?

Widline In my grandma’s case, the fact that she died young is a part of that, but accessibility plays a big role in it as well—at that time, they had no access to the tools to make photographs.

Patrice Helmar (clockwise from top), Berth, 2015; Men & Lifeboats at Dry Dock, 2015; Husky at the Imperial, 2017

Do you have a lot of family history recorded in your family?

Patrice On my mom’s side for sure. This thing has happened as my mom and my aunties get older they seem to be more interested in genealogy. It’s kind of broken up because they came over from Ireland. Can you trace back your family for a ways?

Widline No, in my case my grandparents are as far back I can go. I’ve been meaning to talk to my mom about her grandparents and the ones before that, but I’ve never heard her speak about any of that. Do you think that plays a role in the work that you’re making, and in photographing your family members?

Patrice I have my dad’s mom’s name as my middle name and I consciously use it when I have shows, or publish. Her Greek name was Aphrodite. I get to live this life that she didn’t. She had to work, and I have access to things that she didn’t.

Patrice On my mom’s side for sure. This thing has happened as my mom and my aunties get older they seem to be more interested in genealogy. It’s kind of broken up because they came over from Ireland. Can you trace back your family for a ways?

Widline No, in my case my grandparents are as far back I can go. I’ve been meaning to talk to my mom about her grandparents and the ones before that, but I’ve never heard her speak about any of that. Do you think that plays a role in the work that you’re making, and in photographing your family members?

Patrice I have my dad’s mom’s name as my middle name and I consciously use it when I have shows, or publish. Her Greek name was Aphrodite. I get to live this life that she didn’t. She had to work, and I have access to things that she didn’t.

Both of my grandmothers had a life that wasn’t so easy, and I have a responsibility to make photographs of where I’m from.

Do you feel motivated because there aren’t these photographs of your grandparents, and there’s not this history?

Widline Definitely, that’s one of the primary reasons for making the work that I do. One of the saddest things is to be forgotten.

Patrice A lot of photography is leaving a record that you were here.

Widline How do you view Dirty Old Town, compared to the rest of your practice and other bodies of work?

Patrice I have a responsibility to my town, and I don’t want to screw up. What about you? How does Home Bodies fit into your overall practice as an artist?

Do you feel motivated because there aren’t these photographs of your grandparents, and there’s not this history?

Widline Definitely, that’s one of the primary reasons for making the work that I do. One of the saddest things is to be forgotten.

Patrice A lot of photography is leaving a record that you were here.

Widline How do you view Dirty Old Town, compared to the rest of your practice and other bodies of work?

Patrice I have a responsibility to my town, and I don’t want to screw up. What about you? How does Home Bodies fit into your overall practice as an artist?

Widline It’s going to continue to be something that I do for a very long time. Maybe for the rest of my life. I also think it was a good starting point.

Patrice It takes years…

Widline Definitely.

Patrice I don’t know when I’m going to be done.

Widline It’s also hard to be done when it’s such a personal work.

Patrice I sort of felt like I had it wrapped up. And then you know, life happens. And even then this discussion with you is a real gift. I realize that I have a lot more work to do. I ask that my students make work that is personal. I have to go deeper.

Widline I don’t see a light at the end of the tunnel, yet. Maybe it’s just the process—that’s the thing.

Patrice It takes years…

Widline Definitely.

Patrice I don’t know when I’m going to be done.

Widline It’s also hard to be done when it’s such a personal work.

Patrice I sort of felt like I had it wrapped up. And then you know, life happens. And even then this discussion with you is a real gift. I realize that I have a lot more work to do. I ask that my students make work that is personal. I have to go deeper.

Widline I don’t see a light at the end of the tunnel, yet. Maybe it’s just the process—that’s the thing.

Widline Cadet, M.’s Dog in Doorway, 2014

Widline Cadet is a Haitian-born image-maker based in New York. Her photographic practice is deeply rooted in her experience as an immigrant and explores the racial and cultural tensions as well as identity shifts that sometimes occur due to displacement. Through portraits, landscapes and still life, she uses photography as a means of placing herself and her community. She is the recipient of a 2013 Mortimer-Hays Brandeis Traveling Fellowship and is currently an MFA candidate at Syracuse University's School of Visual and Performing Arts.

Patrice Aphrodite Helmar (b. 1981, Juneau, Alaska) is an artist and independent curator who lives and works in New York City. Helmar's work has appeared internationally, including the Jewish Museum, National Museum of Iceland, Houston Center for Photography, Fisher Landau Center, Judith Charles Gallery, and the Anchorage Museum. Helmar's independent curatorial projects include: Marble Hill Camera Club

(2016 - present day), Backyard Biennial (2017, anticipated 2019).