BETWEEN MYTH

AND REALITY

Ben Huff (Juneau, Alaska) and Karolina Karlic (Santa Cruz, California) have a typical twenty-first century artist relationship, in that it exists entirely online. Huff’s work with Atomic Island, and Karlic’s work with Rubberlands, both investigate isolated communities. This particular conversation took place via email in February and March of 2018.

Ben Huff, (clockwise from top) Patriot Rock, 2018; Target with T-shirt, 2018; Fighter Jet Stickers, 2018, (all) from Atomic Island

Karolina Karlic Can you describe how your projects emerge and then become objects like in your last monograph, The Last Road North? For this project, you took your camera on the road for five years along Alaska’s Dalton highway, a storied stretch of road along the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

Ben Huff I’m interested in taking on something that scares me a little in its scope, something I don’t understand but find a thread to pull on—the thread that interests me is the politics of an exploited landscape. I have a list of a dozen stories here that I intend to explore during my career and the ones that stick are the ones that keep me up at night. Whether it’s oil, technology, or the military, I’m interested in how we use and abuse space. However, I’m only interested in it on the human scale and visually the politics become subtle as I find the nuance of the place. This will sound corny and overly romantic, but I really need to love a place, and photography gives me the time to feel a place deeply and to see it more clearly.

Karolina Regarding The Last Road North and your current work, Atomic Island, could you discuss the role and function of your photographs? Do you see them as archival records, poetry, or something else?

Ben I intend for the end result to be something close to poetry. I want there to be lingering questions and ambiguity in the feeling of the whole of the work but also for there to be clarity in the individual pictures.

Whatever the form, it’s all a mode of bearing witness. I try to keep that in perspective, as I simultaneously try to complicate the narrative. I’m making pictures in order to see what’s there, try to make sense of it for myself, and make a piece of art that conveys some of what I feel but not necessarily what I’ve learned. I’m reminded of James Baldwin's quote, that art’s purpose is “to lay bare the questions which were hidden by the answers.”

Whatever the form, it’s all a mode of bearing witness. I try to keep that in perspective, as I simultaneously try to complicate the narrative. I’m making pictures in order to see what’s there, try to make sense of it for myself, and make a piece of art that conveys some of what I feel but not necessarily what I’ve learned. I’m reminded of James Baldwin's quote, that art’s purpose is “to lay bare the questions which were hidden by the answers.”

Ben Huff, (clockwise from top left) Mile 83: Midnight Light, Driving South, 2012; Mile 177: Brian's Suit, 2012; Mile 175: Sign, Old Man Camp, 2008; Mile 179: Help, 2010, (all) from The Last Road North

Karolina Outsiders have come to understand Alaska with a particular vision that is most likely somewhere between a sculpted myth and the reality.

Ben I’m a photographer living and making work in Alaska, and I’m committed to a life of work here. I recognize that by making pictures here, I’m in some part adding to that mythology. I’m drawn to places that are difficult to get to and which attract “end of the road” types of people. Although I’m always an outsider, I feel comfortable in the challenges of those situations and with the people I photograph. But I’ve come to realize that one of the reasons I take on longer projects, other than the fact that I’m just slow at making work, is that I need to be in a place long enough for it not to be exotic anymore. What I’m looking for is something beyond the easy pictures and on to something that feels more sincere.

Karolina The Alaska I have experienced is one that is aware of the ways in which man must adapt to survive in the landscape. People “conquer the landscape” by the use of ATVs, customized snowmobiles, they even utilize airplanes as a means of delivering pizza—yes, pies in the sky—to isolated communities in Alaska like Nome.

Ben This place is built for hyperbole, and I’m often guilty of it. I’d like to touch just a minute on your reference to “conquering the landscape,” and I’d push that a bit to say that we can live in harmony with the landscape, and we can damage the landscape, but we are not truly capable of conquering it. The landscape doesn’t need us.

Yet, Alaska is built on the idea of the conquest. The conquest of people and of landscapes. The money is made by drilling holes and building roads, pipelines, dams, and mines. I’m a white male who wasn’t born here. In some ways my work is a way of interrogating, or at least recognizing, my own history.

Yet, Alaska is built on the idea of the conquest. The conquest of people and of landscapes. The money is made by drilling holes and building roads, pipelines, dams, and mines. I’m a white male who wasn’t born here. In some ways my work is a way of interrogating, or at least recognizing, my own history.

Karolina I agree, this concept of conquering emerges from conquest, which emerges from colonialism and the acquiring of assets. How would you differentiate Alaska and its history from that of the American West?

Ben In this way, Alaska is no different than the Western United States, and I’m increasingly interested in those similarities.

Karolina Yes, America’s last frontier…

Ben Huff, Mile 318: Boulder and Broken Rail, 2012, from The Last Road North

Ben

Exactly. I have this internal dialogue about the history of this place photographically. After buying the territory from Russia in 1867, Alaska wasn’t accepted as a state until 1959. The geographic advantages for the military were a major strategic influence in statehood. When Alaska became a state, it took on an American identity. It’s no doubt my own ego and geographic history that clouds this thought, but I see Alaska through the lens of being a part of the Western United States. Alaska isn’t unique in its environmental and military missteps. It’s this parallel and the artistic lineage that I’m interested in. The Last Road North, at its core, was a story about our relationship with oil. Latent Landscapes deals with the psychology of technology and distance, and Atomic Island deals with the military complex adapted to the Alaskan landscape.

With long-term projects, I look for spaces that are charged with histories that I find compelling, if not confounding, and that I know will challenge the way I view the landscape. I like that there is no easy way out photographically. My world opened up once I embraced the idea that I could love something fiercely but at the same time be a critic of it.

With long-term projects, I look for spaces that are charged with histories that I find compelling, if not confounding, and that I know will challenge the way I view the landscape. I like that there is no easy way out photographically. My world opened up once I embraced the idea that I could love something fiercely but at the same time be a critic of it.

Karolina Are there other photographers that have pictured Alaska in this particular way—making a larger social commentary?

Ben There are a small handful of talented and hard working photographers here, making lasting work, and several more who come North regularly to make work about Alaska...

But if we go back to the idea of the Union and your question about the larger social commentary, I’ve been thinking a lot about photographers who have used Alaska as a part of a broader visual story of America. I’m leaving out some here, but if we think about Joel Sternfeld with American Prospects, Mitch Epstein’s American Power, Friedlander’s America by Car, Zoe Strauss’ America, and Alec Soth’s The Last Days of W—they all used pictures of Alaska in their representations of America. None of them glorified the space or held it up as something “other.” Sternfeld’s picture of the blind man in his garden in Homer or his picture of the Matanuska Glacier was given no more weight, for instance, than his picture of the boy sitting on the hood of his car in Kansas City or a coal train in West Virginia. I’m drawn to that visual neutrality.

But if we go back to the idea of the Union and your question about the larger social commentary, I’ve been thinking a lot about photographers who have used Alaska as a part of a broader visual story of America. I’m leaving out some here, but if we think about Joel Sternfeld with American Prospects, Mitch Epstein’s American Power, Friedlander’s America by Car, Zoe Strauss’ America, and Alec Soth’s The Last Days of W—they all used pictures of Alaska in their representations of America. None of them glorified the space or held it up as something “other.” Sternfeld’s picture of the blind man in his garden in Homer or his picture of the Matanuska Glacier was given no more weight, for instance, than his picture of the boy sitting on the hood of his car in Kansas City or a coal train in West Virginia. I’m drawn to that visual neutrality.

Ben Huff, (clockwise from top left) Navy Officer Board, 2017; Jack, 2017; Rocks, North Shore, 2017, (all) from Atomic Island

Karolina I’d like to discuss your project Atomic Island in relationship to the greater Alaskan landscape. How did you first arrive on the Island of Adak? How would you describe the 14 Aleutian Islands in the Pacific Ocean, and how did you arrive at making pictures of Alaska's southernmost town, where the Bering Sea meets the Pacific Ocean?

Ben I decided to make work in Adak during my making of The Last Road North. I stumbled onto Stan Cohen’s The Forgotten War in a bookstore in Fairbanks around 2009, and the imagery stopped me cold. My knowledge of WWII history didn’t include the bombing of Dutch Harbor or the Japanese occupation of the westernmost islands of the chain—Attu and Kiska. When I came to a page where there were pictures of Adak and a notation that the island went on to expand into an important outpost in the Cold War, I decided there, in that bookstore, that Adak would be the place of my next long-term project.

Karolina I see similarities in this old American military town to American company towns, boomtowns, and even the Japanese internment camps that were built during WWII. Can you please discuss your interest in the Cold War?

Ben I grew up during the Cold War, in a small conservative Midwest town. The neighborhoods in Adak feel oddly familiar, as they’re intended to. You could drop them in most small suburbs in the 1970s, and they’d fit in. The Aleutians are as wild, romantic, and mythical as any place on earth—it’s the suburbanization of that landscape that I find interesting. Although there were military structures on several islands during WWII, Adak is the only island that had a permanent military population of any size during the Cold War. Incidentally, it was a town built entirely by, and for, the military. It’s an island closer to Russia than Anchorage, and the airport and harbor were military run. It was fully isolated from the outside world, in that if you weren’t military or a registered civilian, you weren’t getting on the island. It had one purpose—protect Americans from communism and the possibility of nuclear war.

I started the work in July of 2015, and the current administration has only intensified my relationship with the place. I can’t shake the fact that Adak was once the Westernmost front of American democracy and is now in physical shambles—the symbolic parallels are a bit on the nose but potent.

I started the work in July of 2015, and the current administration has only intensified my relationship with the place. I can’t shake the fact that Adak was once the Westernmost front of American democracy and is now in physical shambles—the symbolic parallels are a bit on the nose but potent.

Ben Huff, Classroom with Chalkboard (Penis), 2016, from Atomic Island

Karolina In Atomic Island there are photographs that picture the relics of the U.S. military and the houses that once were occupied by many its military families. Many post industrial cities, sites of natural disasters, and sites of extraction have suffered economically and environmentally, and their decay is the subject of many artists and photographers. The popular language for this type of photography, “ruin porn,” is based on aesthetics and is usually devoid of people. For me, your photographs from Adak move beyond the sensationalism of decay and uses documentary photography in a different way.

Ben I’ve been pushing against the idea of “ruin porn” from the beginning. It would be easy to make work that only spoke to the ruins and the shear wastefulness of the entire military operation on Adak, but it would miss the mark.

On the surface, Adak looks like it could share a similar story to Andrew Moore’s Detroit, for instance, but the details are quite the opposite. At the height of the Cold War, Adak housed over 7,000 people. In April of 1997, the base was closed, and within months the island was empty. The Navy decided that a landscape, a geopolitical location, which once was of vital importance was no longer useful. So they left.

The population of that island was only there for one reason. In Detroit (I’m being overly simplistic here) if a GM plant shut down, there were thousands of people out of work and that affected the entire community and other businesses. As those people left, homes were foreclosed, families split up, and other businesses shuttered. It has a ripple effect that reaches into other neighboring communities, as well as businesses all over the country that supply or rely on that GM plant. Adak is different in that the entire island was there in service of the Navy.

The Navy didn’t layoff thousands of workers; they relocated. And because it’s the Federal Government, they could walk away from billions of dollars in infrastructure. The scale of the waste is staggering. Other than the small percentage of former military housing that is currently occupied, every building on the island is rotting, infected with mold, and crumbling. When we talk about military budgets, we talk about jets, ships, and foreign wars. After Adak, I think about washing machines, refrigerators, carpet, linoleum, and roofing shingles. Nails and screws. Forks and spoons.

Building supplies were barged great distances, and armies of civilian contractors were used to build Adak—to make an inhospitable island a booming suburban town which enjoyed a McDonald's, two indoor swimming pools, a bowling alley, a movie theater, and nuclear warheads. The US Military is big business with an unlimited budget, a boss in the American government that spins every failure into a success and which has little accountability for cleaning up the places they’ve destroyed and/or abandoned.

It would be easy to make ruin porn, but the thing that makes me emotionally able to spend multiple years making work in Adak is the small, diverse group of people who have moved in to occupy the abandoned space. People who are trying to fashion their own American dream out of the remnants and exploit the inherent uniqueness of their geography and landscape. It would be easy to look at the place and be cynical, and I occasionally succumb to that, but to stop there would be misguided.

I’m curious as to how you navigated a similar issue. The thing that strikes me about your Rubberlands work, is how delicate it feels. Your mixing of archival photos, rubber plant still lifes, and especially your portraiture has such a light touch, that the potency in the totality of the work snuck up on me, and still surprises. You’ve found a hopefulness, which in the same environment I don’t think most photographers would find, or focus on if they did. How did you come to this way of interpreting the space?

On the surface, Adak looks like it could share a similar story to Andrew Moore’s Detroit, for instance, but the details are quite the opposite. At the height of the Cold War, Adak housed over 7,000 people. In April of 1997, the base was closed, and within months the island was empty. The Navy decided that a landscape, a geopolitical location, which once was of vital importance was no longer useful. So they left.

The population of that island was only there for one reason. In Detroit (I’m being overly simplistic here) if a GM plant shut down, there were thousands of people out of work and that affected the entire community and other businesses. As those people left, homes were foreclosed, families split up, and other businesses shuttered. It has a ripple effect that reaches into other neighboring communities, as well as businesses all over the country that supply or rely on that GM plant. Adak is different in that the entire island was there in service of the Navy.

The Navy didn’t layoff thousands of workers; they relocated. And because it’s the Federal Government, they could walk away from billions of dollars in infrastructure. The scale of the waste is staggering. Other than the small percentage of former military housing that is currently occupied, every building on the island is rotting, infected with mold, and crumbling. When we talk about military budgets, we talk about jets, ships, and foreign wars. After Adak, I think about washing machines, refrigerators, carpet, linoleum, and roofing shingles. Nails and screws. Forks and spoons.

Building supplies were barged great distances, and armies of civilian contractors were used to build Adak—to make an inhospitable island a booming suburban town which enjoyed a McDonald's, two indoor swimming pools, a bowling alley, a movie theater, and nuclear warheads. The US Military is big business with an unlimited budget, a boss in the American government that spins every failure into a success and which has little accountability for cleaning up the places they’ve destroyed and/or abandoned.

It would be easy to make ruin porn, but the thing that makes me emotionally able to spend multiple years making work in Adak is the small, diverse group of people who have moved in to occupy the abandoned space. People who are trying to fashion their own American dream out of the remnants and exploit the inherent uniqueness of their geography and landscape. It would be easy to look at the place and be cynical, and I occasionally succumb to that, but to stop there would be misguided.

I’m curious as to how you navigated a similar issue. The thing that strikes me about your Rubberlands work, is how delicate it feels. Your mixing of archival photos, rubber plant still lifes, and especially your portraiture has such a light touch, that the potency in the totality of the work snuck up on me, and still surprises. You’ve found a hopefulness, which in the same environment I don’t think most photographers would find, or focus on if they did. How did you come to this way of interpreting the space?

Karolina I became even more sensitive to the ways in which photographers were being asked to participate in the production of media journalism when in 2009, Time Magazine launched a year long series that would cover "The Tragedy of Detroit", a story that was close to home for me personally. In some ways, it was all too late to tell the story of Detroit and the same headline had been used on the cover of The New York Times magazine, 20 years earlier in 1990.

Detroit had been overlooked for so long. There was a sense of protection and pride from local Detroiters, filled with fears of exploitation that the media might bring to an already exploited people. I don’t think that the term “ruin porn” is a very good one to address the issues in picturing post-industrial ruin or decay. I believe the artist has a social responsibility to take a critical look at the effects we have had on the earth, and the communities, diasporas, that have been affected by imperial powers and industry. I think our work has common threads in pointing to sites in which the American ideal and values are imposed onto a foreign landscape. In your case the the Aleutian Island in the middle of the Pacific and mine, the Amazonian jungle and Brazilian forests.

In Rubberlands, I set out to continue my investigations of Fordism in Brazil’s rubber plantations in an attempt to render the layered human systems behind capitalism. Rubberlands is not an actual place one can locate on a map but rather a place for contemplating and mapping the ways in which rubber manufacturing is socially, ecologically and systemically formed.

Detroit had been overlooked for so long. There was a sense of protection and pride from local Detroiters, filled with fears of exploitation that the media might bring to an already exploited people. I don’t think that the term “ruin porn” is a very good one to address the issues in picturing post-industrial ruin or decay. I believe the artist has a social responsibility to take a critical look at the effects we have had on the earth, and the communities, diasporas, that have been affected by imperial powers and industry. I think our work has common threads in pointing to sites in which the American ideal and values are imposed onto a foreign landscape. In your case the the Aleutian Island in the middle of the Pacific and mine, the Amazonian jungle and Brazilian forests.

In Rubberlands, I set out to continue my investigations of Fordism in Brazil’s rubber plantations in an attempt to render the layered human systems behind capitalism. Rubberlands is not an actual place one can locate on a map but rather a place for contemplating and mapping the ways in which rubber manufacturing is socially, ecologically and systemically formed.

Karolina Karlic, Emilly Farias in the rubber groves, April, 2014, Michelin Rubber Plantation, Bahia, Brazil

Karolina Karlic, Incised rubber tree latex No. 1, May, 2014/2018, Michelin Rubber Plantation, Bahia, Brazil

Connecting the company archives of Henry Ford, Goodyear, Goodrich, General Tire and Firestone, I found myself tracing the evolution of an industry that relies heavily on outsourcing of the Hevea brasiliensis (Amazonian rubber tree). My photographic fieldwork in Brazil has taken me to photograph manufacturing plants in Salvador and Itaparica, Michelin rubber plantations in the Atlantic forest, a fisherman’s village on the coastal rivers of Itubera in Bahia and the vestiges of Henry Ford's planned community in the Amazon.

Rubber and photography both were integral components of the second phase of the industrial revolution. As I conceptualized my approach in the making of Rubberlands, I thought of the work of photographers such as Thomas Struth’s Paradise pictures and Eliot Porter’s early use of color picturing nature and having studied with Allan Sekula, I desired to insert my own perspectives on globalization and the environment by looking closer at the commodity or rubber and its relationship to the Midwest, where I grew up.

At that time, I had recently watched Alexander Payne’s film, Nebraska. I was so impressed with the use of black and white in the moving picture depicting living room interiors of middle America, families of Billings, Montana, that I also wanted to challenge myself to photograph in monotone in a place that is regularly illuminated with bright greens reflecting the wet dark rainforest.

Most of the portraits in the work are collaborations with the families living and working on the rubber plantation located in Bahia, Brazil, best known for its research in cloning rubber trees in an attempt to create a tree that is more resilient to the South American leaf blight that had infected the Brazilian native plant soon after tree growers started cultivating the species in plantation form.

Rubber and photography both were integral components of the second phase of the industrial revolution. As I conceptualized my approach in the making of Rubberlands, I thought of the work of photographers such as Thomas Struth’s Paradise pictures and Eliot Porter’s early use of color picturing nature and having studied with Allan Sekula, I desired to insert my own perspectives on globalization and the environment by looking closer at the commodity or rubber and its relationship to the Midwest, where I grew up.

At that time, I had recently watched Alexander Payne’s film, Nebraska. I was so impressed with the use of black and white in the moving picture depicting living room interiors of middle America, families of Billings, Montana, that I also wanted to challenge myself to photograph in monotone in a place that is regularly illuminated with bright greens reflecting the wet dark rainforest.

Most of the portraits in the work are collaborations with the families living and working on the rubber plantation located in Bahia, Brazil, best known for its research in cloning rubber trees in an attempt to create a tree that is more resilient to the South American leaf blight that had infected the Brazilian native plant soon after tree growers started cultivating the species in plantation form.

Karolina Karlic, Hevea brasiliensis, rubber tree graft in plastic bag No. 1 & No. 2, April, 2014, Michelin Rubber Plantation, Bahia, Brazil.

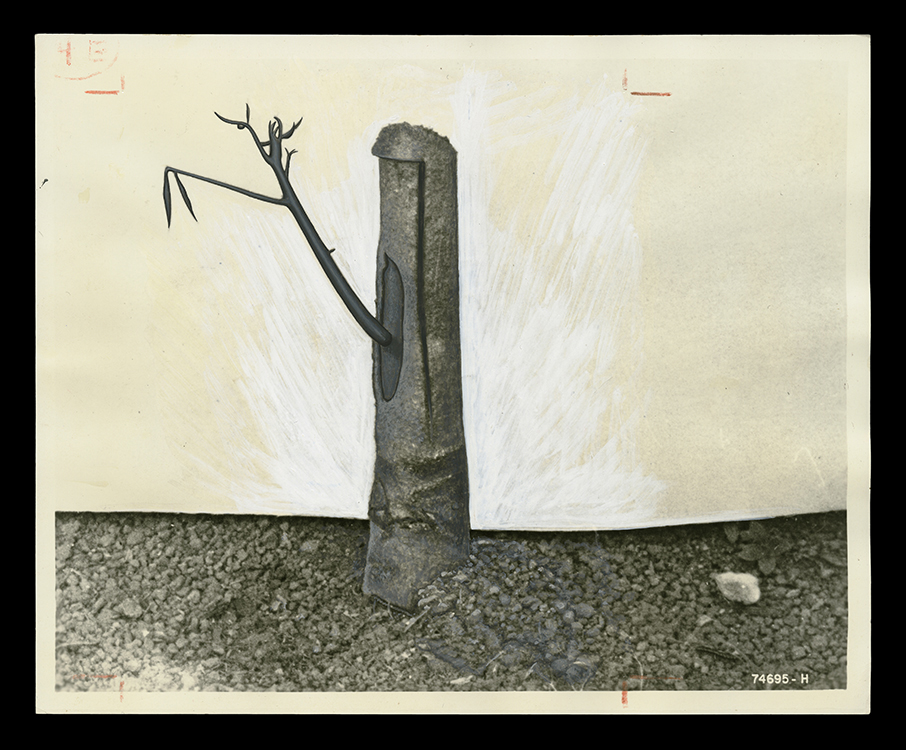

![]() Karolina Karlic, "Grafted Rubber Tree, Fordlandia," Fordlandia, Brazil (1940). Typed on verso: "Ford News - February "A Jungle Conquest." Credit: Companhia Ford Industrial Do Brasil Ford Motor Company. From the Collections of The Henry Ford

Karolina Karlic, "Grafted Rubber Tree, Fordlandia," Fordlandia, Brazil (1940). Typed on verso: "Ford News - February "A Jungle Conquest." Credit: Companhia Ford Industrial Do Brasil Ford Motor Company. From the Collections of The Henry Ford

Getting back to your question more directly Ben, I knew early on that I wanted to show something more of the present in this work verses depicting the “once was” of Henry Ford. While I did photograph Fordlandia in the Amazon, I was less interested in telling a story picturing the ruins of the old hospital or the relics left behind in the jungle. In a way, I was more interested in what I could learn from the scientists, the botanists, the environmentalists and the communities living within rubber-lands today, and was geared more towards a story that would encompass the USA’s Midwest history with the present lives of individuals entwined with rubber manufacturing and Nature. I guess I was more interested in the Brazilian perspective more than anything else. I even started to reference the research photographs that I located in the company archives of Henry Ford, Goodyear, Goodrich, and Firestone by recreating my own contemporary versions of them like in the “Grafted Rubber Tree” and “Hevea brasiliensis, rubber tree graft in plastic bag No. 1 & No. 2” photographs.

The Farias and Souza family daughters invited me into their family homes on the Bahian rubber plantation located in the Atlantic forest. It was through this group of three sisters (Ingrid, Emilly, Ivna) and a young man named Júnior Santos that I became familiar with the forest through a lens that felt collaborative rather than a singular lens of me photographing them. I guess this is what allowed me to partially remove myself from the equation even though I don’t believe a photograph can remove the photographer.

In many ways, Rubberlands is a return to looking at my own relationship to nature and to looking closely at light. I wanted to picture labor through my own lens, a female perspective. In Rubberlands, I related most to the young females growing up in a place of industry.

The Farias and Souza family daughters invited me into their family homes on the Bahian rubber plantation located in the Atlantic forest. It was through this group of three sisters (Ingrid, Emilly, Ivna) and a young man named Júnior Santos that I became familiar with the forest through a lens that felt collaborative rather than a singular lens of me photographing them. I guess this is what allowed me to partially remove myself from the equation even though I don’t believe a photograph can remove the photographer.

In many ways, Rubberlands is a return to looking at my own relationship to nature and to looking closely at light. I wanted to picture labor through my own lens, a female perspective. In Rubberlands, I related most to the young females growing up in a place of industry.

Karolina Karlic (from top), Sisters Ivna and Ingrid Souza playing with cousin Monick Farias in the family backyard with squash plants in the foreground at company housing complex Vila 4; Ivna and Lara playing house inside the Farias family home at company housing complex Vila 4, (both) April, 2014, Michelin Rubber Plantation, Bahia, Brazi

[Getting back to your work,] there is one particular portrait that I’d like to discuss. It’s of a young boy in a snowsuit sitting on the ground. It’s clear the snow has drifted from the wind, and in the background you can see barrack style military structures of the old military base of Adak. For me, this portrait is particularly revealing because of the ways in which it informs me, as a viewer, of your position as a photographer in that space, your awareness, and your desire to tell the story of the people that still occupy a town that was most likely intended not to last in the first place. Can you discuss your intent and what this photograph means for you?

Ben Yes, Isaiah. It’s interesting that you chose this portrait, as my short time with Isaiah was a bit of a turning point in the work. That portrait was the beginning of an effort to focus (not exclusively, but to become more aware) of the children and to be, maybe, more tender in my approach.

School-aged children make up almost a quarter of the permanent population of less than one hundred people, and they provide a counter to the weariness of the detritus. On that particular trip in March of 2016, I felt like I turned a corner in my relationship with the community—I felt a little less like an outsider, that people no longer viewed me as a journalist who would come out once or twice and go away to write a story about the pitiful ghost town of Adak.

Specifically, about the portraits, they’re a combination of choreography, chance, and cooperation. He was holding the piece of grass in his hand, and earlier he was in a snowball fight with his brother. I watched him for a short time and asked him to mimic a bit in that play, and in the moment I saw them as symbols for weapons. I couldn’t have planned the camo gloves and hat. I left that experience, that portrait, feeling as though my perspective of the whole of the work to that point might have shifted just a bit.

School-aged children make up almost a quarter of the permanent population of less than one hundred people, and they provide a counter to the weariness of the detritus. On that particular trip in March of 2016, I felt like I turned a corner in my relationship with the community—I felt a little less like an outsider, that people no longer viewed me as a journalist who would come out once or twice and go away to write a story about the pitiful ghost town of Adak.

Specifically, about the portraits, they’re a combination of choreography, chance, and cooperation. He was holding the piece of grass in his hand, and earlier he was in a snowball fight with his brother. I watched him for a short time and asked him to mimic a bit in that play, and in the moment I saw them as symbols for weapons. I couldn’t have planned the camo gloves and hat. I left that experience, that portrait, feeling as though my perspective of the whole of the work to that point might have shifted just a bit.

Ben Huff, Isiah, 2017, from Atomic Island

Ben Huff, Esther, Kulluk Bay on the 4th of July, 2017, from Atomic Island

Karolina In another photograph, you picture a figure walking out into the sea. Can you tell me more about this photograph and your process in making photographs with the community of Adak residents?

Ben That is a picture of Esther in Kulluk Bay, with the Bering Sea on the horizon.

I made that picture last year on the 4th of July. I went over the holiday, specifically, to see the town’s small parade, fireworks, and the vision I had of the stars and stripes against the backdrop of the abandoned military complex. Most of the day yielded absolutely abysmal weather, but much of the town still showed up for the afternoon beach party. It was pouring rain, there was a fair amount of drinking, and I couldn’t find what I was looking for. With the drinking, people became more aware of the camera, and I often feel uncomfortable when I can’t sort of slink off and talk to people one on one. Even now that I’m making relationships there, I’d much rather set out looking for moments to present themselves, rather than scheduling them. I had kind of resigned to the fact that the day was a bust. Then I look up and see Esther had escaped, and she was down the beach a hundred yards, walking out into the bay. I was told later that she does it every year on the 4th of July. It was magical. While everyone else was partying, she was having this beautiful moment of tradition for herself.

I made that picture last year on the 4th of July. I went over the holiday, specifically, to see the town’s small parade, fireworks, and the vision I had of the stars and stripes against the backdrop of the abandoned military complex. Most of the day yielded absolutely abysmal weather, but much of the town still showed up for the afternoon beach party. It was pouring rain, there was a fair amount of drinking, and I couldn’t find what I was looking for. With the drinking, people became more aware of the camera, and I often feel uncomfortable when I can’t sort of slink off and talk to people one on one. Even now that I’m making relationships there, I’d much rather set out looking for moments to present themselves, rather than scheduling them. I had kind of resigned to the fact that the day was a bust. Then I look up and see Esther had escaped, and she was down the beach a hundred yards, walking out into the bay. I was told later that she does it every year on the 4th of July. It was magical. While everyone else was partying, she was having this beautiful moment of tradition for herself.

Ben Huff, Munitions Bunkers, 2018, from Atomic Island

Karolina I’m curious what your subjects believe will happen to the future of Adak island?

Ben They’re enjoying a bit of optimism lately, as an outside company has come in to resurrect the failed fish processing plant, and new quotas have been released in both the Pacific Cod and King Crab fishery. By every indication, this might be a lifeline for them, but it’s a scenario that’s played out before with only short-term success. They have had many economic carrots dangled in front of them but few materialize. It’s complicated, but I have hope they can turn it around.

Karolina In photography there is often a story that is unseen or impossible to photograph. If you could tell us the story you weren’t able to picture, what would it be?

Ben I feel like I’m always working in the margins of the subject, thinking about how much I can leave out to still make it work.

Your question is on my mind constantly with Atomic Island, as the Naval base was a nuclear submarine surveillance base. Submarines are ghosts. I feel like I’m on this constant scavenger hunt, but the person who was supposed to leave things to be found took the day off.

However, more specifically, Adak had 120-foot-tall White Alice radio towers on the island during the Cold War. One of the first pictures I saw of Adak was of those towers. They’re such an emblem of the Cold War, and I was excited to make pictures of them. I was dispirited on my first trip to find that they were no longer there. They were destroyed and buried in 1987. It was a bit of an auspicious start, as I realized early on that there weren’t many visual markers left of the story I wanted to tell.

But that’s the beauty of photography—it’s all an allusion. How do I communicate the thing, without showing the thing? It’s a riddle with no answer, and it’s the thing that keeps me coming back.

Your question is on my mind constantly with Atomic Island, as the Naval base was a nuclear submarine surveillance base. Submarines are ghosts. I feel like I’m on this constant scavenger hunt, but the person who was supposed to leave things to be found took the day off.

However, more specifically, Adak had 120-foot-tall White Alice radio towers on the island during the Cold War. One of the first pictures I saw of Adak was of those towers. They’re such an emblem of the Cold War, and I was excited to make pictures of them. I was dispirited on my first trip to find that they were no longer there. They were destroyed and buried in 1987. It was a bit of an auspicious start, as I realized early on that there weren’t many visual markers left of the story I wanted to tell.

But that’s the beauty of photography—it’s all an allusion. How do I communicate the thing, without showing the thing? It’s a riddle with no answer, and it’s the thing that keeps me coming back.

︎

Karolina Karlic was born in Wroclaw, Poland, immigrated to Detroit, Michigan in 1987, and holds an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts and a BFA from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. She is an Assistant Professor in the Art Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she currently resides. She is the recipient of numerous fellowships and awards and her series, Rubberlands, is currently on view at Light Work, in Syracuse, New York.

Ben Huff was born in LeClaire, Iowa, migrated to Colorado in his 20's and moved to Fairbanks, Alaska in 2005. He currently lives with his wife in Juneau. His first monograph, The Last Road North, was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2014.

He's had solo exhibitions at the Pratt Museum, Alaska State Museum, Museum of the North and Newspace in Portland, Oregon. Among other accolades, he received Alaska Humanities Forum grants in 2015 and 2016 for his work in the region.

Karolina Karlic, "Grafted Rubber Tree, Fordlandia," Fordlandia, Brazil (1940). Typed on verso: "Ford News - February "A Jungle Conquest." Credit: Companhia Ford Industrial Do Brasil Ford Motor Company. From the Collections of The Henry Ford

Karolina Karlic, "Grafted Rubber Tree, Fordlandia," Fordlandia, Brazil (1940). Typed on verso: "Ford News - February "A Jungle Conquest." Credit: Companhia Ford Industrial Do Brasil Ford Motor Company. From the Collections of The Henry Ford