IT

USED

TO

WAKE

YOU

UP

ON REPRESENTATION AND RESPONSIBILITY

Sasha Phyars-Burgess Let me explain to you my headspace. When I saw that we were going to have this conversation, I was pumped for it. I figured that we were probably going to talk about race since the premise was “How can we, as photographers, start a conversation about the communities that we're photographing and the people that live in them underneath this current administration?” I've been feeling since the election and even before the election: "When are white people going to do the work and do it in a way that creates change?" I don't actually know if it's possible for them to do it in this system.

Juan Madrid Yeah, I don't know either. One thing that's been weighing heavily on me for some time is portraiture, especially from white men who travel to some area in the US, often impoverished, and document life there. It's often done without humanity—apart from what the photo world regards as humanity—and with little regard for the person being photographed. Between that and seeing and having conversations regarding the objectification of Black bodies and other people of color, I'm curious to what you think about people who have higher levels of privilege taking photographs of others with less privilege, whether it be due to gender, race, class, or any other reason or combo of the above.

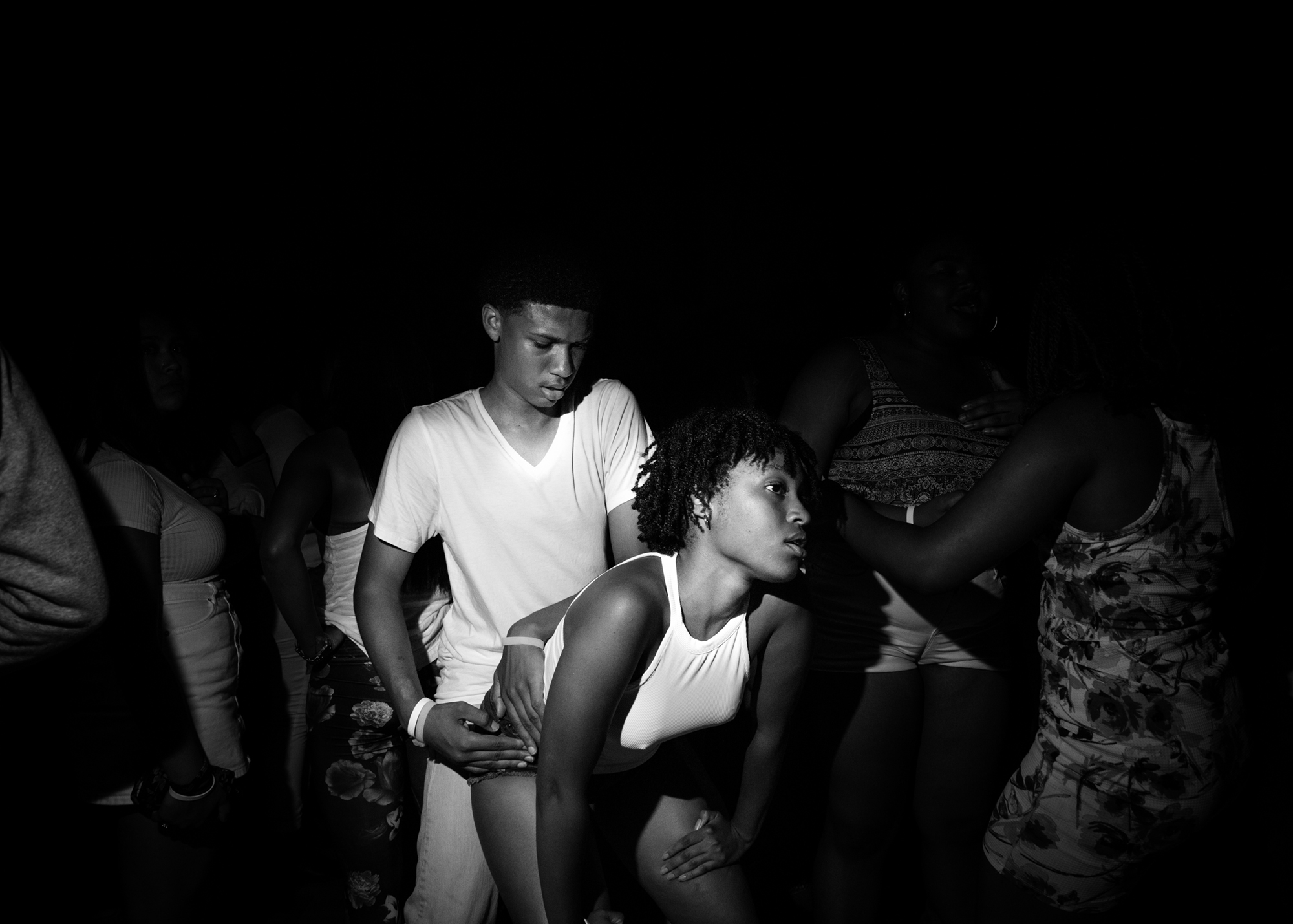

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, All White Party I, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2016

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, All White Party I, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2016

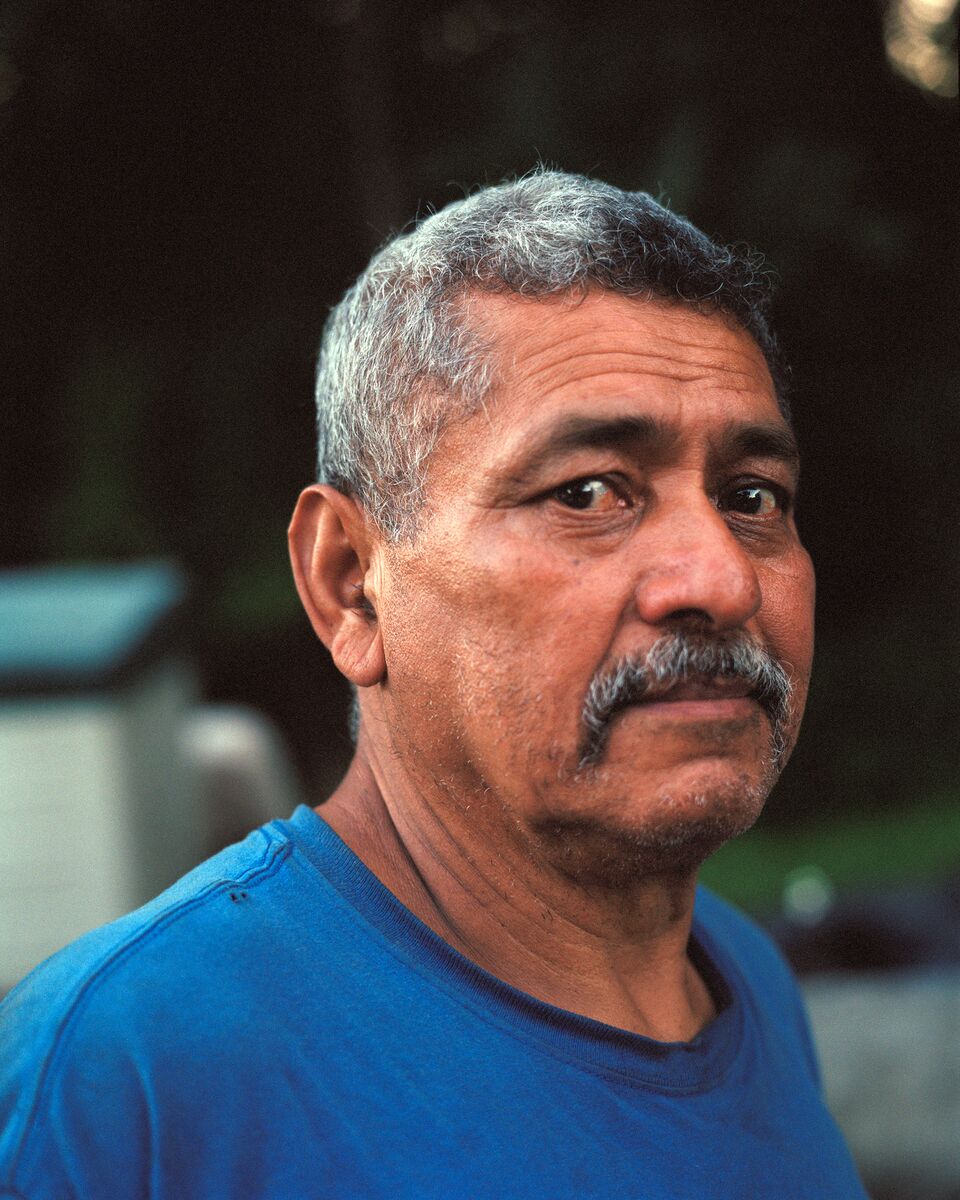

Juan Madrid, Untitled, 2017

Juan Madrid, Untitled, 2017Sasha I'm curious to know your thoughts about this. Why has it been weighing on your mind recently? Why now?

Juan One of my professors at RIT was Greg Halpern and he was a huge influence while I was there, but after getting out of college and finishing the work I was doing in Flint, I definitely started questioning more my own place in that whole portraiture thing. For a while, I just couldn't make portraits of people. I've slowly gotten back into it, but the thing is, photography is already an exploitative medium, and it's really strange to keep piling more exploitation on top of it. In the end, it seems like it just ends up being about consumption instead of community or the community it does benefit is a photo world—art world kind of community. The question is: Can you actually bring that other community in? The community that's being photographed, that is.

Sasha Those are all the things that I'm thinking about and struggling with as well.

Juan Recently, I worked on a newsprint about Flint with photographer Brett Carlsen that we “Kickstarted.” To us, it was a no-brainer to donate everything we got from selling it because otherwise we'd just be continuing that cycle of capitalism, consumption, and exploitation. Even though donating the money is not really breaking that cycle, we are at least trying to offset it a little bit. However, it doesn't wipe out the exploitation. I've thought about whether or not some exploitation can be positive or at least…

Sasha Uhh... Whoa...

Juan Can you have humanity without exploitation or is it just not possible?

Juan One of my professors at RIT was Greg Halpern and he was a huge influence while I was there, but after getting out of college and finishing the work I was doing in Flint, I definitely started questioning more my own place in that whole portraiture thing. For a while, I just couldn't make portraits of people. I've slowly gotten back into it, but the thing is, photography is already an exploitative medium, and it's really strange to keep piling more exploitation on top of it. In the end, it seems like it just ends up being about consumption instead of community or the community it does benefit is a photo world—art world kind of community. The question is: Can you actually bring that other community in? The community that's being photographed, that is.

Sasha Those are all the things that I'm thinking about and struggling with as well.

Juan Recently, I worked on a newsprint about Flint with photographer Brett Carlsen that we “Kickstarted.” To us, it was a no-brainer to donate everything we got from selling it because otherwise we'd just be continuing that cycle of capitalism, consumption, and exploitation. Even though donating the money is not really breaking that cycle, we are at least trying to offset it a little bit. However, it doesn't wipe out the exploitation. I've thought about whether or not some exploitation can be positive or at least…

Sasha Uhh... Whoa...

Juan Can you have humanity without exploitation or is it just not possible?

Sasha Ok. First off, I'm going to look up the definition of exploitation just to wrap my head around the question.

"The act or fact of treating someone unfairly in order to benefit from their work. The action of making use of and benefiting from resources."

I'm going to say no because this is an imperialist argument; this is a colonial argument. Like, yeah, we did these things to you, but it was for your betterment. I see where it comes from, and so I have to be like: No! Then I think about what the documentary photography world has yet to address and what sometimes the art photography world does address, but usually only photographers of color address it. They address the history of photography itself because the history of photography is the issue with photography. The history of the image is the issue with the image. That's why you and I continually are coming up against this wall because we know that the history of photography is a history of exploitation. It’s the history of knowledge that's not necessarily true.

"The act or fact of treating someone unfairly in order to benefit from their work. The action of making use of and benefiting from resources."

I'm going to say no because this is an imperialist argument; this is a colonial argument. Like, yeah, we did these things to you, but it was for your betterment. I see where it comes from, and so I have to be like: No! Then I think about what the documentary photography world has yet to address and what sometimes the art photography world does address, but usually only photographers of color address it. They address the history of photography itself because the history of photography is the issue with photography. The history of the image is the issue with the image. That's why you and I continually are coming up against this wall because we know that the history of photography is a history of exploitation. It’s the history of knowledge that's not necessarily true.

Juan Do you know Cristina de Middel's Afronauts?

Sasha Yeah, I do.

Juan I read an interesting point from Carla Williams and Meron Menghistab having a conversation about the fact that she's not Black, but she's portraying these Black bodies. She's using the history of that country's attempt to make history, because she was interested in it and not because she had an actual connection to it. I've seen a lot of people come to consensus that, since she's an artist and has an interest in it, then she can make art about it. However, the entire other side is that she has access to resources that somebody from that country may not have, even though they have that personal connection and that history. It's weird how photography deals with history—its own history and history itself—and how it seems so disconnected from it.

Sasha Yeah, I do.

Juan I read an interesting point from Carla Williams and Meron Menghistab having a conversation about the fact that she's not Black, but she's portraying these Black bodies. She's using the history of that country's attempt to make history, because she was interested in it and not because she had an actual connection to it. I've seen a lot of people come to consensus that, since she's an artist and has an interest in it, then she can make art about it. However, the entire other side is that she has access to resources that somebody from that country may not have, even though they have that personal connection and that history. It's weird how photography deals with history—its own history and history itself—and how it seems so disconnected from it.

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, All White Party II, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2016

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, All White Party II, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2016

Sasha It's always an issue. If I hypothetically say I'm interested in the Belarus Space Mission in 1942 and it predated the US Space Invasion, then go to Belarus—first of all, I couldn't even take my ass to Belarus. There are so many levels to it, right? It's not just that she has the resources to do things like that. It's that her physical body presents access. If I take my ass to Belarus, I start walking around, and I say, "I'm interested in the 1942…" people would be like, "Get your ass out of here!" People would probably be terrified of me. For me to gain access into these spaces and to take those kinds of photographs would be twenty times harder than it would be for a person with a different skin color than me. That's just the truth. De Middel mostly takes photographs of Black people, doesn't she?

Juan She's done stuff in Brazil as well and she just moved to Mexico. She's originally from Spain.

Sasha Yeah... I mean, it's also like, are people not allowed to be interested in people other than themselves? I don't know, but I question it. I question the exoticism of it all and what it is that people find so compelling. But, of course, we want to see the world. That's why we're interested in things that involve looking because we are looking at the world and we're questioning it. I guess I just have questions about uncritical thought around these things. I'm not sure how critical de Middel is being about the things that she can do or colonial looking.

Juan She's done stuff in Brazil as well and she just moved to Mexico. She's originally from Spain.

Sasha Yeah... I mean, it's also like, are people not allowed to be interested in people other than themselves? I don't know, but I question it. I question the exoticism of it all and what it is that people find so compelling. But, of course, we want to see the world. That's why we're interested in things that involve looking because we are looking at the world and we're questioning it. I guess I just have questions about uncritical thought around these things. I'm not sure how critical de Middel is being about the things that she can do or colonial looking.

Juan Yeah, even if she is being critical about it, she's being neo-colonial in her gaze, even if she doesn't mean to. Despite all of the access she has, it's also who has access to her work. The first book she made sold out and became a thousand dollar book on the secondary market. She just published a second edition and I think it's already sold out. She's making it for a very specific world, so it's a commodity. It's feeding into this elitism, and it's almost feel-good. It's like you've done something, but you haven't really. It's just accumulation of knowledge without actual action. Can photography move beyond that or is it just stuck?

Sasha I don't know. I think about this all of the time. Lewis Hine, he got shit done. Vietnam War photography got shit done. Right? I think a lot of white people saw white children getting beat up by police and they were upset. I think that expedited it—the end of the war. It didn't expedite it enough, but it did expedite it.

Juan If I'm not mistaken, Lewis Hine considered himself an activist and not a photographer.

Sasha Well, yeah. That's the only type of effective photography. Art photography is not very effective.

Juan A perfect time to bring up this David Hammons quote that you may already know. "Doing things in the street is more powerful than art I think. Because art has gotten so... I don't know what the fuck art is about now. It doesn't do anything. Like Malcolm X said, it's like Novocain. It used to wake you up but now it puts you to sleep. I think that art now is putting people to sleep. There's so much of it around in this town that it doesn't mean anything. That's why the artist has to be very careful what he shows when he shows now. Because the people aren't really looking at art, they're looking at each other and each other's clothes and each other's haircuts."

Sasha I don't know. I think about this all of the time. Lewis Hine, he got shit done. Vietnam War photography got shit done. Right? I think a lot of white people saw white children getting beat up by police and they were upset. I think that expedited it—the end of the war. It didn't expedite it enough, but it did expedite it.

Juan If I'm not mistaken, Lewis Hine considered himself an activist and not a photographer.

Sasha Well, yeah. That's the only type of effective photography. Art photography is not very effective.

Juan A perfect time to bring up this David Hammons quote that you may already know. "Doing things in the street is more powerful than art I think. Because art has gotten so... I don't know what the fuck art is about now. It doesn't do anything. Like Malcolm X said, it's like Novocain. It used to wake you up but now it puts you to sleep. I think that art now is putting people to sleep. There's so much of it around in this town that it doesn't mean anything. That's why the artist has to be very careful what he shows when he shows now. Because the people aren't really looking at art, they're looking at each other and each other's clothes and each other's haircuts."

Sasha That is a pretty strong indictment. Sometimes I feel like I agree with it and sometimes I feel that I don't. Art is another thing that says it's outside of the system, but it's not—the white cube, and even with photos. The idea of showing art in a space that's totally devoid of any characteristics of the world such as dirt or things that signify the world coming in. It gives people the notion that art is separate from the world and, for that reason, a lot of artists do these things that they believe show the system. They replicate the system because they believe they are outside of the system, but they're not.

Can you tell me about your Flint work?

Juan It's a lot different than how I work now.

Sasha Can you talk about that difference?

Juan The big one is that I don't photograph people quite as much. I was talking to people a lot more in Flint. Maybe it's also just the landscape of American society these days, but people seem more distant. It's also that I haven't resolved the whole idea of commodifying another person to tell their story when I know I can't tell their story.

Sasha What work are you making right now?

Juan I've been working around Catskill and now Kingston for the past three or four year, just wandering around. I've been making portraits of my girlfriend, too, and that's been a learning experience.

Can you tell me about your Flint work?

Juan It's a lot different than how I work now.

Sasha Can you talk about that difference?

Juan The big one is that I don't photograph people quite as much. I was talking to people a lot more in Flint. Maybe it's also just the landscape of American society these days, but people seem more distant. It's also that I haven't resolved the whole idea of commodifying another person to tell their story when I know I can't tell their story.

Sasha What work are you making right now?

Juan I've been working around Catskill and now Kingston for the past three or four year, just wandering around. I've been making portraits of my girlfriend, too, and that's been a learning experience.

Juan Madrid (from top, all untitled), 2013; 2017; 2017; 2017

Sasha Why is that a learning experience?

Juan I have to confront issues with my own gaze, which I hadn't had to do as much because I had photographed mostly strangers previously.

Sasha I think this is actually an important thing that you're saying because I'm coming from the opposite direction. I photographed my family first, and now I'm trying to photograph people in the world. How did you come to start photographing in the world first? What is it like now to photograph your girlfriend and, if I'm not mistaken, also your dad?

Juan Yeah, I wanted to start a project photographing him, and I want to make photographs of my mom, too.

Sasha Right, so you started out in the world, and then you’re returning to your family and the people that are closest to you. I'm interested. How did you start photographing in the world?

Juan I picked up a camera towards the end of high school and just never did that whole photograph my family, photograph my friends kind of thing. Also, I don't have a super tight knit family, so it's not like it ever made sense to just pick up a camera and take photos of everybody. Then, the past year or two, I've been getting more interested in my own personal history and realizing just how much of a disconnect that there's been, and I think that photography is the easiest, or best way at least, for me to go about that. With regards to photographing strangers, part of it was about going out and finding and learning things. I think I've become a little bit less interested in that with thinking so much about exploitation, with thinking about using another person’s image, and whether or not you have any right to use another person's image without their permission. It's just trying to be more aware. I think what photography really needs these days is more awareness. What's it like for you coming from the opposite end?

Juan I have to confront issues with my own gaze, which I hadn't had to do as much because I had photographed mostly strangers previously.

Sasha I think this is actually an important thing that you're saying because I'm coming from the opposite direction. I photographed my family first, and now I'm trying to photograph people in the world. How did you come to start photographing in the world first? What is it like now to photograph your girlfriend and, if I'm not mistaken, also your dad?

Juan Yeah, I wanted to start a project photographing him, and I want to make photographs of my mom, too.

Sasha Right, so you started out in the world, and then you’re returning to your family and the people that are closest to you. I'm interested. How did you start photographing in the world?

Juan I picked up a camera towards the end of high school and just never did that whole photograph my family, photograph my friends kind of thing. Also, I don't have a super tight knit family, so it's not like it ever made sense to just pick up a camera and take photos of everybody. Then, the past year or two, I've been getting more interested in my own personal history and realizing just how much of a disconnect that there's been, and I think that photography is the easiest, or best way at least, for me to go about that. With regards to photographing strangers, part of it was about going out and finding and learning things. I think I've become a little bit less interested in that with thinking so much about exploitation, with thinking about using another person’s image, and whether or not you have any right to use another person's image without their permission. It's just trying to be more aware. I think what photography really needs these days is more awareness. What's it like for you coming from the opposite end?

Sasha It's really difficult. I guess I do come from more of a tight knit family. I'm just thinking in relation to what you said. I started out photographing my friends and my family first because those were the people that I felt most comfortable around and I didn't feel super comfortable in the world. I think that's something that I feel often when I look at the canon of white, male, cisgendered—I'm assuming fairly hetero—photographers that were in the street that had so much agency in the street that I just don't have. I just feel different in the street. In spending so much time looking at these things and wishing that I could be that way in the street and then having to be like, "You can't. Your body is not that body." Sometimes people look at my photos and I get a comment about the way people are looking toward the camera—or rather, looking at the viewer, right? It took me a long time to realize this in a stupid way, but I was like, "Oh, they're looking like that because they're looking at me." I think that's something that we forget. The way that the person in the image is looking out into the world—who they're looking at is really the photographer. So the way that people react to me and my body is completely different to the way that they're going to react to even you or a white man. There's a whole other thing that's happening there. I don't know why it took me so long to realize that. When my body comes up to someone and asks for a photograph, it's a different thing that happens, a different expectation, I think. It's not about me personally; it's about my body that they see. I don't believe that photographers believe that they are invisible anymore because I think we are beyond that. We have to be.

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, Kelechi in the Hallway, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 2017

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, Kelechi in the Hallway, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 2017

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, Abby and Friend, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2017

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, Abby and Friend, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 2017

Something that I think isn't talked about enough is the way that people react to our physical beings. I'm a 5'5" Black woman that presents as a teenager in the right situation. People are reacting to me. It's just different. When I photographed in Pennsylvania for a long time, especially when I was photographing in Allentown and in Bethlehem, all the places that I grew up, people were reacting to me as a familiar sight. Even when people said no, they weren't treating me differently than any other person that was in their neighborhood. They didn't think I was a professional. They didn't think that I was someone to be feared. This past winter I was in Apopka, Florida and I was driving around one night. It was New Year's Eve, and people were setting off fireworks. In this neighborhood in Apopka it's predominantly Black. I pull over, get out, and ask some people, "Oh, hey. Can I take some photographs?" They're just like, "Yeah, sure," because they're reacting to me. If I had been a white man in that situation, they would have been like, "What are you doing here?" They would have thought it was for something professional. You know what I'm saying? I was doing it for school and I told them, "I'm in school. I'm doing this work for school. I'll send you the photographs." I told them all that kind of stuff. They're like, "Yeah." But, really, when I'm spending time with them, when I'm just standing on the corner with them, when the people across the street look at us, they're not going to see me as any different from those people. My presence there is not out of the ordinary. So, when people see me, there they're just like, "Yeah, do what you want. We don't really even care." They don’t care because they're reacting to my body. Sometimes there are class perceptions with this, too. If you're of a certain class and you're white and you go into a white neighborhood and you're not of that class, those people are going to react to you in a different way, just like my class sometimes, even when I'm in certain Black neighborhoods. People react to that class. They react to my body, and they also react to my class. Maybe one of the most powerful things that we can do is return to ourselves the way that you're doing, return to who we are, and realize that we bring those bodies everywhere and that people react to those bodies.

Juan That's really important to say. I don't know if people think about that a lot. I wasn't thinking about it a ton when I was working in Flint. Part of it was still being in college, still being kind of dumb, and not always thinking things through. The amount of privilege I had then and having people tell me about their lives, part of it was because of how I look. Also, I had someone showing me around the city, but I only had access to that because somebody else had access to somebody who could get me help. It was different from when I was walking around there alone. Depending on where I was, people were more friendly or less friendly. Our bodies dictate a lot in photography.

Sasha You can say a lot about where you lie politically, but it's important to remember also where your body lies politically and what happens when you bring that body.

Juan I was having a discussion with a friend this past summer, and I was being a little facetious. I was trying to instigate a bit, and I was like, "White people should just stop making art," because I've seen other people saying that. I don't know how serious they are, but I think some of them are at least semi-serious. With the oversaturation of imagery, especially in the documentary subset, do we really need all of that? You're making it for the same people over and over again. It's not for the people you're photographing. Don't lie to yourself and say that it is. I think it comes down to awareness. Rather than producing for the sake of production, produce for yourself and your community. Maybe it's time to stop thinking so globally.

Sasha You can say a lot about where you lie politically, but it's important to remember also where your body lies politically and what happens when you bring that body.

Juan I was having a discussion with a friend this past summer, and I was being a little facetious. I was trying to instigate a bit, and I was like, "White people should just stop making art," because I've seen other people saying that. I don't know how serious they are, but I think some of them are at least semi-serious. With the oversaturation of imagery, especially in the documentary subset, do we really need all of that? You're making it for the same people over and over again. It's not for the people you're photographing. Don't lie to yourself and say that it is. I think it comes down to awareness. Rather than producing for the sake of production, produce for yourself and your community. Maybe it's time to stop thinking so globally.

Sasha What if your community is other people just like you?

Juan I think it's just a form of capitalism then, and there isn't any way out of that. It's always going to be about commodity. The photobook world, I mean, you're making photobooks for other photobook viewers. You're not making it for anybody else. So just take away the materiality, the physicality of that, and what do you do if you're only making photographs for photographers? Maybe you shouldn't make photographs and find something better to do with your time. Going back to the original question in this conversation about community, maybe it's about taking action. It's about doing the work, and it's not about hiding behind photobooks or digital platforms. They can be useful tools, but when they become the whole object of the process, then who are you helping? Are you just helping yourself? And are you even doing it in a healthy way? It's hard to shoot down other people's ideas of community because maybe they do get something out of it that's valuable to them.

Juan I think it's just a form of capitalism then, and there isn't any way out of that. It's always going to be about commodity. The photobook world, I mean, you're making photobooks for other photobook viewers. You're not making it for anybody else. So just take away the materiality, the physicality of that, and what do you do if you're only making photographs for photographers? Maybe you shouldn't make photographs and find something better to do with your time. Going back to the original question in this conversation about community, maybe it's about taking action. It's about doing the work, and it's not about hiding behind photobooks or digital platforms. They can be useful tools, but when they become the whole object of the process, then who are you helping? Are you just helping yourself? And are you even doing it in a healthy way? It's hard to shoot down other people's ideas of community because maybe they do get something out of it that's valuable to them.

Juan Madrid & Sasha Phyars-Burgess in conversation