OUR NEW JERSEY

Caiti Borruso, Glass Picture, 2015

Michael J. Dalton II, Broken Glass, 2012

Caiti Borruso I meet Michael at an opening in LIC on the first of September. He is from New Jersey, which makes my ears prick up, and he has a copy of his book, The Great Falls. We huddle under a single streetlight somewhere on a side street looking through it, and I am staring at the map of Paterson thinking about my own maps. When he tells me about his upbringing, I realize he might be the only person who could understand my relationship to Jersey in its entirety. I leave with questions. A month later I visit Paterson for the first time.

Michael J Dalton There is something about making photos in New Jersey that sort of makes me feel melancholic, nostalgic, and curious. It probably comes from the complicated relationship that I have with the place, as we all have with the places we come from... I was transplanted from Maine into the state at the age of 11 after my mother was sent to prison for repeated drug offenses. So my introduction to living in NJ was a little bumpy in the beginning. But I love NJ and think of my experiences there fondly. I still love driving around Passaic, Union, Essex, Hudson, and Middlesex counties to find pictures and just explore. I mean, I also check out other counties, but I keep going back to that area frequently. Counties are funny in NJ. They sort of seem like mini-States.

Where did you grow up in NJ? What are your favorite places to make photos and why? Do you go back these days?

![]()

Michael J. Dalton II, Family Hanging out at a 7-11, 2014

Caiti Making pictures in Jersey has been difficult over the past year. My mother sold my childhood home last year, and we were out of it by March 31st. I grew up in the remnants of a shore town; the homes were built to be modest summer homes. I lived in the attic of a Cape Cod, essentially, from age 5 to 23. The neighborhood was cobbled together, the backyards touch at strange intersections, and there's a lake called Treasure Lake, shaped like an X, a small seawall, and beyond that, the bay. But I was born in Red Bank, and I spent the first three years of my life in Point Pleasant, which is a proper shore town, with fireworks at the beach every Wednesday night. My parents divorced when I was three, and my mom moved us north to Cliffwood Beach and bought a house.

Now that the house has sold, my practice has changed. I drive down there now to do something specific, or always stop if I'm making a trip for a different reason. I treat it differently; there is a little more respect, a little more curiosity, a new way of feeling. I am an outsider. I notice the changes more because I see them less, the way you register changes more quickly in people you see twice a year. I used to be able to dictate my moods by the bay's water.

I'll stop for now with two images: one of my childhood bed, and one of Aberdeen-Matawan, which after all these years is no longer my stop on the NJ Coast line, and a question: can you tell me more about the map you made of Paterson?

I'll stop for now with two images: one of my childhood bed, and one of Aberdeen-Matawan, which after all these years is no longer my stop on the NJ Coast line, and a question: can you tell me more about the map you made of Paterson?

Caiti Borruso, Childhood Bed, 2015; Aberdeen Matawan, 2015

Michael J. Dalton II, Stamped Map Print, 2017

Michael That's such an interesting area. I never had a chance to spend much time in that region of Monmouth county. I Google Mapped Cliffwood Beach and Treasure Lake with its X shape and close proximity to the ocean. There was an interesting photo that popped up online—seemed like a huge flood had occurred over a road—maybe from that hurricane you spoke of? I'm so curious… I'm looking forward to checking out that area. I used to visit Sandy Hook a lot when I was younger. We'd take Route 18 to Route 36 up the coast. When my sister and I were in our last years of high school, we skipped a few Friday classes and took that old drive to the shore, even though Asbury Park was a more common beach for us at that time. Back then we had to use maps and our memories. We didn't have cell phones, let alone iPhones with GPS. It became sort of a tradition for me to hit the road and get lost with some friends and find new ways to get home. I often didn't carry a camera back then, as I had little money for film. But I used to love running around like that.

I guess that’s where the map comes in.

When I started working on The Great Falls in 2011, I only had a vague idea about the geography, history, the people and the concept that would become the foundation for my book. There is a big connection to William Carlos Williams’ poem Paterson (Book Four) when he writes, "...Just because there ain't no water fit to drink in that spot (or/ you ain't found none) don't mean there ain't no fresh water to be/ had NOWHERE." I actually started the project by obsessively reading the epic poem, and eventually I realized I had to continually visit Paterson. I walked everywhere around Paterson. I love that city. I would take the Jitney Bus from New York Penn Station to Downtown Paterson at least once or twice a week. I went through every neighborhood on foot, multiple times, finding new people and places to photograph with my Pentax 67, 8x10 in a backpack and a tripod slung on my shoulder.

Even though I really loved the city and the people I met, I wasn't really interested in making a project specifically about a place. That in itself is just the first layer of the project. I found ways to make the project more about an atmosphere or a feeling by finding similar experiences when going to other cities such as Lowell, Massachusetts, Newark, Passaic, Clifton, Brooklyn and even Berlin. After coming back to Patterson over the years to make photographs, I was able to identify themes of resilience, escape, and reclamation (regarding both the people of Paterson and the natural elements of the park). I began to seek these themes in my picture making in other cities as well. This gave me the freedom to conceptually work outside the the confines of focusing on a specific geographic location. I was able to be a bit more playful with the utilization of the suspension of one’s disbelief in a reality of what could be perceived as a documentation of a place. It’s strange because with the attempt to make the location disorienting, I ended up making photographs of other places that look like Paterson. In that sense, I was able to make a view of my own version of Paterson. So with that in mind, I wanted to use a map that had similarities to the actual map of the area of the Great Falls, but again was not exactly the same. I drew the original map from memory. After I completed it, I added numbers to the map that correlate to the original sequence of one of the maquettes I created. I also added directions in the map that lead you on a path I took the day I figured out how to complete the project.

In the limited edition version of The Great Falls, I made a second map. I used two maps—the final hand drawn map with numbers, and a zoomed in section of The Great Falls from a 1913 map. This was the year of the Silk Strike in Paterson during a time when workers were fighting for basic rights, such as 8 hour work days and safe working conditions.

I guess that’s where the map comes in.

When I started working on The Great Falls in 2011, I only had a vague idea about the geography, history, the people and the concept that would become the foundation for my book. There is a big connection to William Carlos Williams’ poem Paterson (Book Four) when he writes, "...Just because there ain't no water fit to drink in that spot (or/ you ain't found none) don't mean there ain't no fresh water to be/ had NOWHERE." I actually started the project by obsessively reading the epic poem, and eventually I realized I had to continually visit Paterson. I walked everywhere around Paterson. I love that city. I would take the Jitney Bus from New York Penn Station to Downtown Paterson at least once or twice a week. I went through every neighborhood on foot, multiple times, finding new people and places to photograph with my Pentax 67, 8x10 in a backpack and a tripod slung on my shoulder.

Even though I really loved the city and the people I met, I wasn't really interested in making a project specifically about a place. That in itself is just the first layer of the project. I found ways to make the project more about an atmosphere or a feeling by finding similar experiences when going to other cities such as Lowell, Massachusetts, Newark, Passaic, Clifton, Brooklyn and even Berlin. After coming back to Patterson over the years to make photographs, I was able to identify themes of resilience, escape, and reclamation (regarding both the people of Paterson and the natural elements of the park). I began to seek these themes in my picture making in other cities as well. This gave me the freedom to conceptually work outside the the confines of focusing on a specific geographic location. I was able to be a bit more playful with the utilization of the suspension of one’s disbelief in a reality of what could be perceived as a documentation of a place. It’s strange because with the attempt to make the location disorienting, I ended up making photographs of other places that look like Paterson. In that sense, I was able to make a view of my own version of Paterson. So with that in mind, I wanted to use a map that had similarities to the actual map of the area of the Great Falls, but again was not exactly the same. I drew the original map from memory. After I completed it, I added numbers to the map that correlate to the original sequence of one of the maquettes I created. I also added directions in the map that lead you on a path I took the day I figured out how to complete the project.

In the limited edition version of The Great Falls, I made a second map. I used two maps—the final hand drawn map with numbers, and a zoomed in section of The Great Falls from a 1913 map. This was the year of the Silk Strike in Paterson during a time when workers were fighting for basic rights, such as 8 hour work days and safe working conditions.

Michael J. Dalton II, (clockwise from top right) Sunday Afternoon, 2013; Guard Rail and the River, 2012; Dead Ducks, 2015; A Young Couple, 2013; A View of Downtown Paterson From Above the Valley of the Rocks (Winter), 2013

My experience living in NJ however was not like the strength and resilience I depict in the people I photograph or the natural environment taking back the landscape. Rather, it was a typical angsty teenage experience, hanging out at convenience store parking lots, malls, skateboarding, partying, trying to stay away from my family as much as possible. But though there was drama and some hard times, I really enjoyed my youth looking back at it. It was aimless and beautiful.

Your projects Whale Creek Is Flooding, Shady Acres, and the New Work are hard to place, geographically, and remind me in ways of the American South or Midwest. I'm fascinated by this, as I tend to be drawn to more industrial or urban landscapes. Do you want your pictures to display a specificity of place or do you seek a sense of geographic ambiguity?

I also like the sense of intimacy in your photos—the picture you shared of your childhood bed, but also the fact that you seem very close to your subjects—there is a comfort and closeness displayed that seems familial. Can you speak a bit on that?

Your projects Whale Creek Is Flooding, Shady Acres, and the New Work are hard to place, geographically, and remind me in ways of the American South or Midwest. I'm fascinated by this, as I tend to be drawn to more industrial or urban landscapes. Do you want your pictures to display a specificity of place or do you seek a sense of geographic ambiguity?

I also like the sense of intimacy in your photos—the picture you shared of your childhood bed, but also the fact that you seem very close to your subjects—there is a comfort and closeness displayed that seems familial. Can you speak a bit on that?

Caiti I actually went to Paterson back in October, about a month after meeting you at Eva [O’Leary]'s opening—I was feeling restless and had been thinking about it and wondering why I hadn't gone. I found these pictures of my grandparents in an album, pictures they had taken of Paterson in the 80s, and wondered why I hadn't gone. So I went, by myself. It was anticlimactic, and I got wet, and I sat alone looking over the falls feeling mildly forlorn. It was hotter than it should have been for October.

I spent time working in Asbury Park and I loved the shit out of it, but Cliffwood is a little different, not for tourists. There used to be a big pirate ship on the side of the road in CWB, off Route 35. I haven't found out that much about it but it's on my list.

![]()

I spent time working in Asbury Park and I loved the shit out of it, but Cliffwood is a little different, not for tourists. There used to be a big pirate ship on the side of the road in CWB, off Route 35. I haven't found out that much about it but it's on my list.

Caiti Borruso, Untitled, 2016, from Shady Acres

It's funny that you mention the poem—when I finally resigned myself to making work about New Jersey (after continually hearing throughout college that I shouldn't be doing that), I started reading Paterson. It felt like research I needed to do; the day I realized that's what I was doing, I bought a copy and started writing in it. I really love the map you made of Paterson, and the retracing of steps, and the frenetic feeling of your map. And I think sometimes by leaving the place you're photographing, you end up learning more about what you expect from it, or need from it, or want from it. I had a similar experience going back to Cliffwood to make Whale Creek is Flooding, what with taking the train back and pacing. So much pacing on foot trying to align myself with something new, trying to belong again.

Whale Creek is one of the boundaries of Cliffwood Beach and of Monmouth County itself, and along the creek two different boys I knew died, one in the parking lot and one further down, where the creek meets the bay. So it isn't work made in the south or the midwest but right outside my back door, in the same spot where I grew up, skinned my knees, did the messy shit. Metaphorical messy shit. It's funny, because it doesn't look like anything to me except what it is. All of the pictures but a handful are made within a one mile radius. (The shadow picture was made in Sayreville, outside of my mother's old warehouse; the red house is just down 35 in a neighborhood my mother's cousin owned homes in, the dogs I found at the Englishtown flea market where my mother used to work.)

Whale Creek is one of the boundaries of Cliffwood Beach and of Monmouth County itself, and along the creek two different boys I knew died, one in the parking lot and one further down, where the creek meets the bay. So it isn't work made in the south or the midwest but right outside my back door, in the same spot where I grew up, skinned my knees, did the messy shit. Metaphorical messy shit. It's funny, because it doesn't look like anything to me except what it is. All of the pictures but a handful are made within a one mile radius. (The shadow picture was made in Sayreville, outside of my mother's old warehouse; the red house is just down 35 in a neighborhood my mother's cousin owned homes in, the dogs I found at the Englishtown flea market where my mother used to work.)

Caiti Borruso (clockwise from top left), Treasure Lake, 2016; The Pit, 2015, Lawrence Harbor, 2015; Mom’s Chair, 2015 (all from Whale Creek)

The Shady Acres work is also a place I'm strongly connected to. My aunt owned a campground in Pennsylvania, and I spent most of my summers there, until I turned fourteen. When I was twenty and living alone, I bought a bus ticket out there and saw most of my family for the first time in six years. The place was exactly the same; it felt like it had held its breath, waiting for me, had gently paused everything but my cousins and their aging. I was welcomed back with open arms but still felt like I didn't belong, and thus the camera: it made everything easier. I photographed there intermittently over three summers, until the campground sold in 2016. It was a project I had wanted to continue forever.

In terms of the new work: I've been going back to Cliffwood and photographing and taking field samples—audio, rubbings. I don't feel like my work is done with the neighborhood. I haven't figured it out yet.

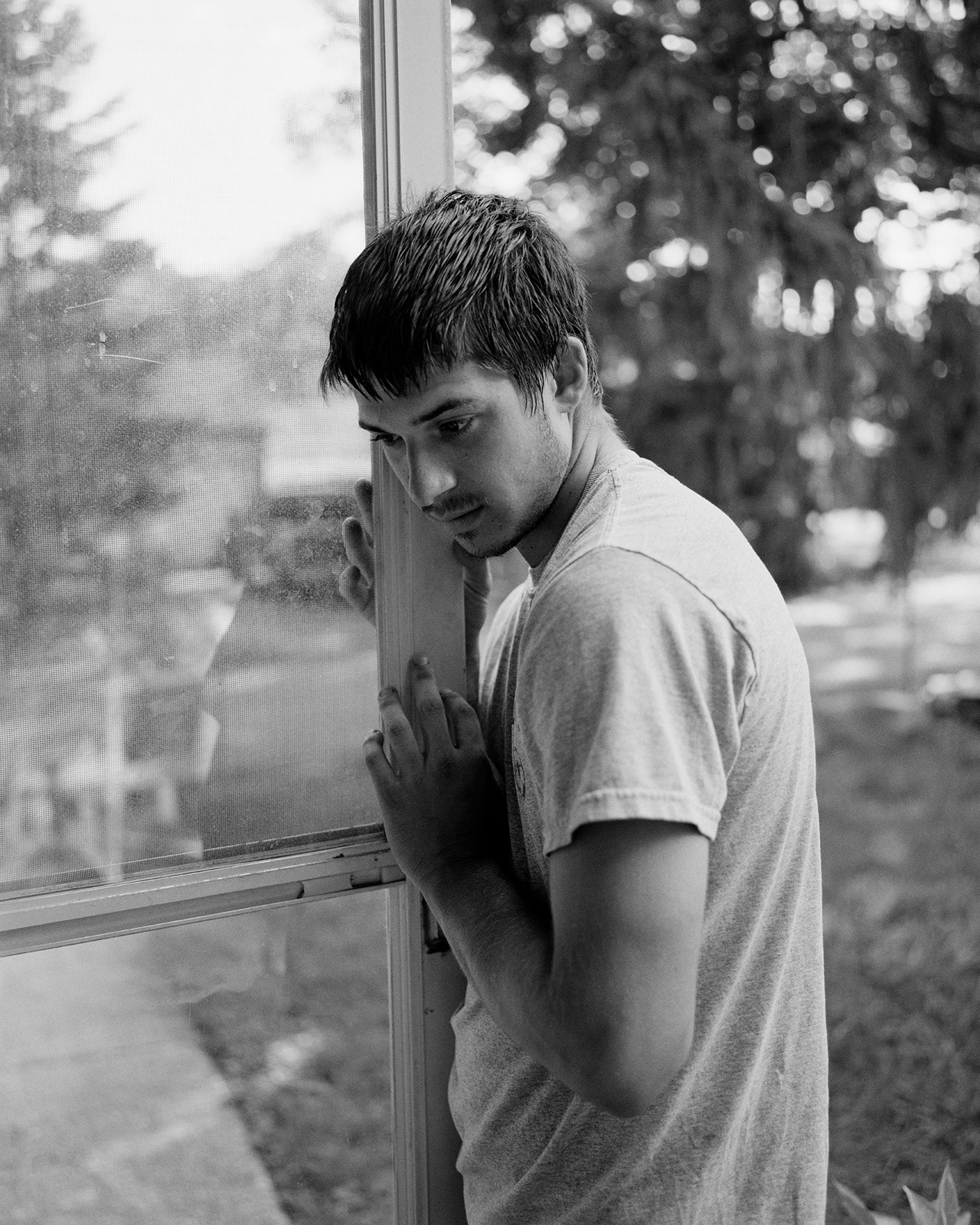

This picture is of my brother at our back door.

In terms of the new work: I've been going back to Cliffwood and photographing and taking field samples—audio, rubbings. I don't feel like my work is done with the neighborhood. I haven't figured it out yet.

This picture is of my brother at our back door.

(clockwise from top) Caiti Borruso, Pat at the back door, 2016; last self portrait (Dana), 2017; last haircut, 2017

My mom cut my hair at the head of our kitchen table my entire life. This was my last day at the house.

And the third image, from the new work, was made in my bedroom in New York in August when I was in the middle of breaking up with my partner at the time. I am surprised, and honored, that he let me act on that impulse.

And the third image, from the new work, was made in my bedroom in New York in August when I was in the middle of breaking up with my partner at the time. I am surprised, and honored, that he let me act on that impulse.

I have been trying to make more portraits, especially of the people that I love, or have stopped loving. I realized recently that, after a few long years of pacing an empty beach, and mostly photographing the ground and myself, I wanted to be with other people, and talk to them, and make their pictures. Tapping into other people feels like a hurdle I am trying to clear, one I have been eyeing nervously for years.

Since we are on the topic—what are you working on? How do you approach portraits? I love everything that's happening in the portrait of the trio—the car, the smoke, the girl pursing her lips like she might be blowing out smoke.

Since we are on the topic—what are you working on? How do you approach portraits? I love everything that's happening in the portrait of the trio—the car, the smoke, the girl pursing her lips like she might be blowing out smoke.

Michael J. Dalton II, Self portrait, 2010

Michael That’s great you’re trying to work outside your comfort zone. Portraits can be challenging. There is a lot involved and, in the immediate sense, more at stake. Not that landscapes or still lives can't be challenging or risky. But in portraiture, we are forced to deal with what we want an image to be about. Your memories of the person, the conversation, everything that happened between you and your subject fogs up what's actually happening in the picture.

With portraits, the more I do it, the less awkward I feel. If I haven't done it in a while, I kind of lose the energy and vision. It's funny though, once I make one portrait during a day, I feel completely ready for the next one. Like I just had to break out of my regularly scheduled program and gain a bit of courage. Once I do that one picture, I'm set for the day. I'll go up to anyone and ask them to do whatever it is I feel like having them do in front of the lens.

Sometimes I feel like I should do more self-portraiture just out of convenience because part of this whole process is time, and time is a challenging problem for me. I mean this literally. I work 40-80 hours a week. More recently, my new projects involve welding and sculpture. I'm also training to become a pipe fitting welder I train for about 2-5 hours each night after work. I'm trying to get my welds perfect. And the time... it's taking forever. But it would be a pay increase so I can afford to continue my artistic practice and pay both my BFA and MFA loans. I actually like the high strung, fast paced experience I’ve made for myself. I think it actually is something that keeps me going. The work ends up being like a freight train, hard to stop.

With portraits, the more I do it, the less awkward I feel. If I haven't done it in a while, I kind of lose the energy and vision. It's funny though, once I make one portrait during a day, I feel completely ready for the next one. Like I just had to break out of my regularly scheduled program and gain a bit of courage. Once I do that one picture, I'm set for the day. I'll go up to anyone and ask them to do whatever it is I feel like having them do in front of the lens.

Sometimes I feel like I should do more self-portraiture just out of convenience because part of this whole process is time, and time is a challenging problem for me. I mean this literally. I work 40-80 hours a week. More recently, my new projects involve welding and sculpture. I'm also training to become a pipe fitting welder I train for about 2-5 hours each night after work. I'm trying to get my welds perfect. And the time... it's taking forever. But it would be a pay increase so I can afford to continue my artistic practice and pay both my BFA and MFA loans. I actually like the high strung, fast paced experience I’ve made for myself. I think it actually is something that keeps me going. The work ends up being like a freight train, hard to stop.

Caiti I’m just heading back from visiting family in Florida and hardly made any portraits, although I want to, desperately. It is a muscle memory, making portraits, one I have started trying to flex again. It’s the same with anything related to pictures though - it’s like breaking the metaphorical seal. I find making portraits anxiety-inducing at first, but then I settle into a space where I hum, bounce, relax into myself around others in a way that doesn’t happen often. It’s nice, then, that the camera lets me do that. It lets me tap into people I haven’t seen, or wouldn’t have taken the time to see, either.

A portrait I have been meaning to make for months now: Damien is the first of the "next generation" of my neighborhood. He is the spitting image of his father and his uncles. I haven't spent a lot of time around babies of people I've known, and it's wild to look at someone's face and realize it came from someone else. I want to photograph the rest of the boys (now men) that I grew up with; I was one of two girls in the neighborhood, and Janel aligned herself with the boys, while I did not.

It’s funny that you say self-portraits out of convenience. Is that one photograph a photo of you (a self-portrait)? I find myself more emotionally drained after making a self-portrait than I do making images of others; I often feel like I am facing myself, my body, challenging myself. I make self-portraits to mark important dates, mostly, or to try and coax myself back into my skin when I feel like I am about to burst out of it.

Time is a really difficult part of making work—I’ve just switched work schedules, and I work on weekends now. It’s giving me time to adapt to having a studio, and developing a practice, but it means my shooting time is when most of the people I’d like to photograph are working.

A portrait I have been meaning to make for months now: Damien is the first of the "next generation" of my neighborhood. He is the spitting image of his father and his uncles. I haven't spent a lot of time around babies of people I've known, and it's wild to look at someone's face and realize it came from someone else. I want to photograph the rest of the boys (now men) that I grew up with; I was one of two girls in the neighborhood, and Janel aligned herself with the boys, while I did not.

It’s funny that you say self-portraits out of convenience. Is that one photograph a photo of you (a self-portrait)? I find myself more emotionally drained after making a self-portrait than I do making images of others; I often feel like I am facing myself, my body, challenging myself. I make self-portraits to mark important dates, mostly, or to try and coax myself back into my skin when I feel like I am about to burst out of it.

Time is a really difficult part of making work—I’ve just switched work schedules, and I work on weekends now. It’s giving me time to adapt to having a studio, and developing a practice, but it means my shooting time is when most of the people I’d like to photograph are working.

Caiti Borruso, Lindsay and Damien, 2018

Michael

Speaking of time, one of the ways I try to make sure I am making as much work as I can is by working on multiple projects at the same time. I can’t stand being unable to make an image because of reasons like weather or accessibility. So, when the time comes, I’ll fluctuate between projects on any given day.

Right now I'm working on a project that I'm temporarily calling Labor. This project has to do with my experience doing manual labor and existing in the blue collar world, which seems to be the complete opposite of what I experience when I drive back to my apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. I work with a lot of conservative, racist, misogynistic baby boomer men from the suburbs of Long Island, Upstate NY, New Jersey and Pennsylvania in environments that are in such contrast from my existence in a racially diverse neighborhood in Brooklyn. In the project, I hope to convey my feelings about this blue-collar culture, and my issues with some of their problematic behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes. At the same time, I want to show my respect for the hard work and dedication that's required to get a check at the end of the week.

In Labor, I am also reflecting on my status as a privileged, educated white male, working in a conservative universe, and my alternate life in a liberal progressive bubble. It’s a work in progress, so the concepts, edit, sequence, and form may change. I’m also bringing in some backup as this project is quite expansive; I’ll be collaborating this time with Aaron Bianco while designing and editing the book. I really dig his style and insight and am excited to complete Labor with him.

Right now I'm working on a project that I'm temporarily calling Labor. This project has to do with my experience doing manual labor and existing in the blue collar world, which seems to be the complete opposite of what I experience when I drive back to my apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. I work with a lot of conservative, racist, misogynistic baby boomer men from the suburbs of Long Island, Upstate NY, New Jersey and Pennsylvania in environments that are in such contrast from my existence in a racially diverse neighborhood in Brooklyn. In the project, I hope to convey my feelings about this blue-collar culture, and my issues with some of their problematic behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes. At the same time, I want to show my respect for the hard work and dedication that's required to get a check at the end of the week.

In Labor, I am also reflecting on my status as a privileged, educated white male, working in a conservative universe, and my alternate life in a liberal progressive bubble. It’s a work in progress, so the concepts, edit, sequence, and form may change. I’m also bringing in some backup as this project is quite expansive; I’ll be collaborating this time with Aaron Bianco while designing and editing the book. I really dig his style and insight and am excited to complete Labor with him.

Michael J. Dalton II, (clockwise from top left) Image Title, 20xx; Photograph From an Old Glass Negative Bought on eBay. I Accidentally Shattered It Shortly After Scanning, 2014; Trenton Makes the World Takes, 2014

Michael J. Dalton II, Bird Photograph #1, 2017

Another photographic project I'm working on is much more intimate, subtle, and quiet. I started going on walks in Prospect Park with my girlfriend Stephanie, who is a poet and is into birding. As we would go on our long walks, she would point out new species of birds to me and sometimes recite poetry she'd memorized (something that has always impressed me). I often brought my camera on these walks and eventually we both had the idea that it would be interesting to make pictures of the birds that Steph would spot and maybe pair them with her writing. The photographs are majoritively landscape images, and in some moments, the bird that I was trying to make a photograph of has already left. This series is so new that it’s both conceptually and photographically incomplete, but it’s sort of is taking a form similar to Friedlander's photographs of vines and leaves—densely patterned flora that covers the entire frame.

I’m also doing a project about one of my siblings, Nik. I’ve been making photographs of Nik since 2011. Maybe even earlier. It’s an ongoing project that I plan to keep working on. It’s really interesting to see someone grow up through photographs as I don’t get to see Nik all the time. I plan on making these pictures for a while.

I’m also doing a project about one of my siblings, Nik. I’ve been making photographs of Nik since 2011. Maybe even earlier. It’s an ongoing project that I plan to keep working on. It’s really interesting to see someone grow up through photographs as I don’t get to see Nik all the time. I plan on making these pictures for a while.

Michael J. Dalton II, (from left) The Gift, 2010; First Communion, 2011

Caiti You remind me of my brother, which is funny. He works as a trucker at a large rigging company in central Jersey. Three weeks ago he rigged some Richard Serra sculptures over on the west side of Manhattan. (Up until January I worked at an art handling/trucking company. After all this time, and my college degree and his lack thereof, we ended up doing mighty similar things, which makes me happy.) He works insane work weeks, like you. I’ve been gently photographing him when I can, but it’s hard to see him, and now our work schedules are misaligned. It’s strange being from Jersey and one of the only people I know from the neighborhood who left Jersey, went to college, no longer lives in the area, etc, etc. I feel responsible for myself, and the way I move throughout the place where I’m from. I felt much more comfortable, in a way, working at an (albeit art centric) trucking company, in a warehouse full of men, than I do now, working at a bookstore in Manhattan. I felt like my mother and brother in the warehouse. I feel much more out of place now, fish out of water. I bought a pair of heels. It’s very strange.

Michael I've always loved the part of NJ that inspires the stupid jokes people will tell you about the place, like, "oh, what exit are you from?" That’s a line that used to make my otherwise very calm grandmother into the serious business, no-funny-stuff-nurse-from-World-War-II grandmother who took no shit from anyone.

I think about the places where you can get a gnarly porkroll, egg, and cheese sandwich at a Krauser’s, or those random delis that also second as bars at night. Route 27 or Route 1. Jersey barriers with weeds growing out of the cracks. All the bridges crossing the Passaic River. The abandoned gas station and strip mall off Route 18. It’s strange how I love the landscape, the detritus, even the suburbs that I swore I’d never live in while I was growing up. Maybe I'd hate it like I did when I was in high school if I moved back.

I tried to do the professional photographer thing, the assistant thing, and attempted to work at an art institution. But by that time I was insanely broke from making art and paying Brooklyn rents. I had to get a steady paying job to afford my bills and art supplies so I went back to construction work. I stopped for a few years while I went to grad school, but now I’m back at it. I’ve been doing it for so long now, I know what you mean when you say it’s strange to put on heels.

I think about the places where you can get a gnarly porkroll, egg, and cheese sandwich at a Krauser’s, or those random delis that also second as bars at night. Route 27 or Route 1. Jersey barriers with weeds growing out of the cracks. All the bridges crossing the Passaic River. The abandoned gas station and strip mall off Route 18. It’s strange how I love the landscape, the detritus, even the suburbs that I swore I’d never live in while I was growing up. Maybe I'd hate it like I did when I was in high school if I moved back.

I tried to do the professional photographer thing, the assistant thing, and attempted to work at an art institution. But by that time I was insanely broke from making art and paying Brooklyn rents. I had to get a steady paying job to afford my bills and art supplies so I went back to construction work. I stopped for a few years while I went to grad school, but now I’m back at it. I’ve been doing it for so long now, I know what you mean when you say it’s strange to put on heels.

︎

Michael Dalton (b. 1985, Marshfield, MA) lives and works in Brooklyn, New York as an artist and construction worker. He received his BFA from The School of Visual Arts and his MFA from The University of Hartford. His work has been exhibited throughout the United States and in Berlin. His new monograph, The Great Falls was published by Peperoni Books (Germany, August 2017), complemented by a solo exbhibit at FKK Gallery (Berlin, May 2018).

Caiti Borruso (b. 1993, Red Bank, NJ) lives and works in three different basements in Brooklyn, NY. On Thursdays she drives to New Jersey and pisses on the side of the road.