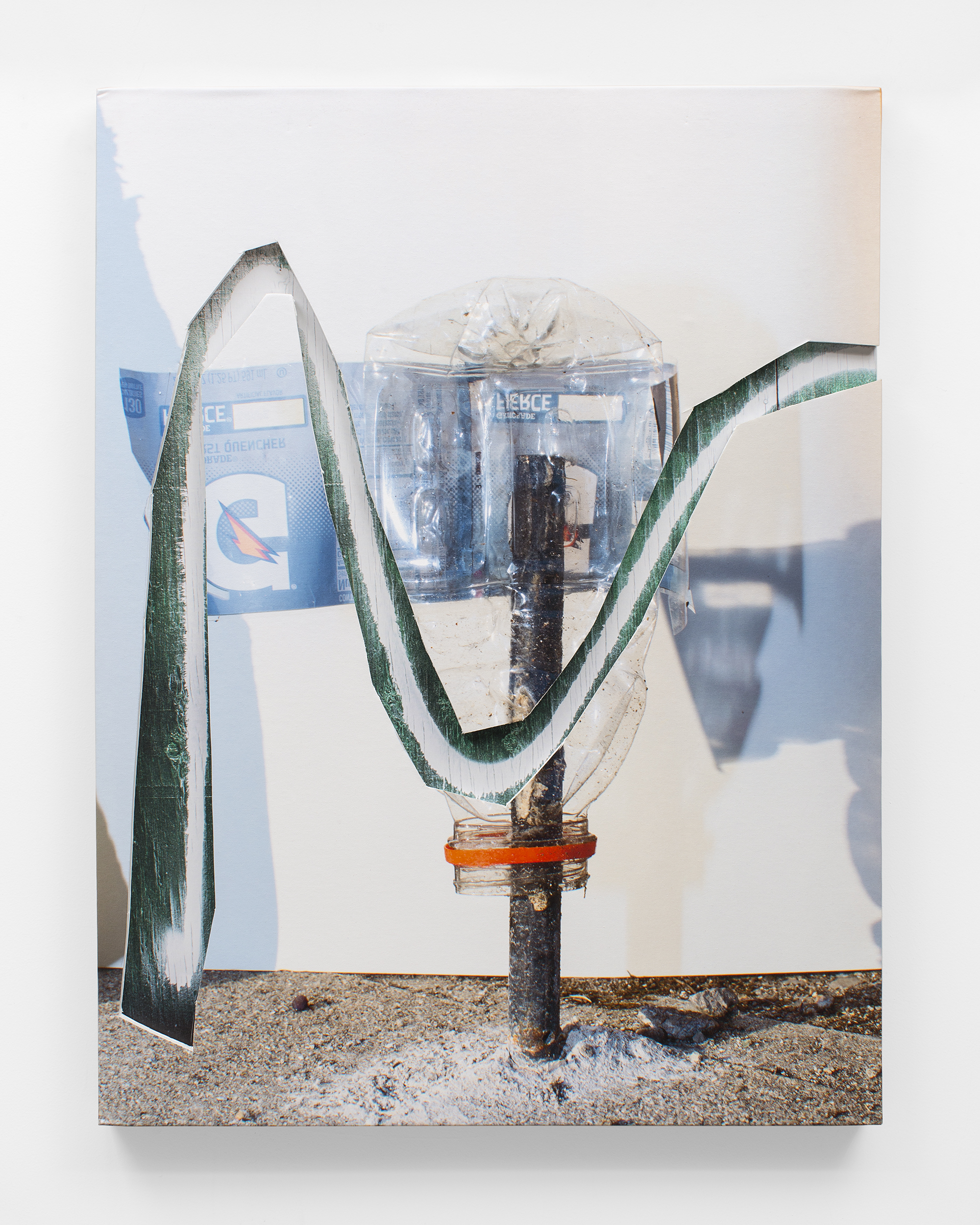

Ilana Savdie, Marital Troubles, 2015

I L A N A S A V D I E

EZM Tell us about bridging the gaps between your photographic, painting, and sculptural practices.

Ilana Savdie I worked for a few years in photography for the fashion and beauty industries, primarily as a retoucher. I was much more interested in the gestural aspect of nipping and tucking bodies with my fingertips and, having come from a background in painting, I was curious about the translation of fingertips into full body gestures. Within the beauty industry, I was often tasked with combing through stock photos to help define infuriating idealisms for marketing teams to sell back to us. Eventually, destroying these images became a form of sketching for me. I have always obsessively collected perfectly retouched images that serve to represent the beauty, health and hygiene industries. Sculptural works became about attempting to make tangible the textures and materials I was consuming behind screens and understand how these interacted with my own body in space.

EZM How does an understanding of these mediums push you and your conceptual motivations for the works? And do you see this mixing and overlaying of mediums as a transgressive act?

IS I always look to Gloria Anzaldua’s definition of defiance. She says it is the “freedom to chisel my own face, to staunch the bleeding with ashes, to fashion my own gods out of my entrails.” Painting and sculpture became another tool with which to protest the impossible textures of predetermined utopias. Material pluralities arrive at a truer texxxture for culturally complicated bodies like mine.

EZM How do you see your work fitting into n e w f l e s h?

IS I think of the queer body as one that arrives at a certain divinity through its own abjection and it is a major driver in my work. The bodies that shape shift to define their own boundaries beyond those imposed upon them, the identities forever in a state of becoming, kept intact in their state of flux. This is where I find form, what drives gesture and how I carve out flesh.

J E S S I C A P E T T W A Y

EZM Your work seems so visually motivated by the unexpected and bizarre. Do you think it’s important to embrace the unusual and maybe even the undesirable? Why?

Jessica Pettway It is so important to embrace the unusual and undesirable in art! Isn’t that just life? Laughing at pain? Having some weird “Charlie Brown moments” pile on top of each other that sometimes you just have to take a second and laugh at the gag of it all? In my work I have a lot of fun making jokes out of the mundane and calling attention to how unusual everyday life can be.

EZM What scares you about your work or the things you experience in the world? Do you see your work as a way to push against anxiety?

JP One source of anxiety is making sure I’m able to leave my mark on this industry as a Black Woman. I’m always grappling with the thought, “What is it like to move in an industry with only slightly more than a handful of people to look up to that look like myself?” All I can do is keep making work that I love and hope that I can help someone that looks like me.

EZM How do you see your work fitting into n e w f l e s h?

JP The photo of mine in n e w f l e s h allows for the possibility of the strange, and presents a fresh take on a bouquet of flowers or an all out garden party. In fragmenting the body, this photo alters our ideas of reality and welcomes the viewer to engage with the unfamiliar.

Jessica Pettway, Garden Party, 2016

KC Crow Maddux, Untitled, 2018

K C C R O W M A D D U X

EZM Can you talk about how you go about making a place or finding a history that speaks to your practice?

KC Crow Maddux History is difficult for me, as very often we look to the past for what people in our communities were making. Being trans and on hormones I am living in what I consider to be a post-human body that is actually something fresh to history. I mostly look to canonized “art history”, which generally speaking is the history of CIS white men, for conventions to work against. The implied neutrality of many structural elements, the rectilinear picture format and the white wall for example, are representative of the naturalized state of the patriarchal gaze or voice. I intersect those conventions from a queer angle; disrupting them with invention. I am developing a trans format.

EZM People talk a lot about art as a way to start a conversation, but I so rarely hear what that conversation is supposed to be about or where/when people should have it. Just that a conversation needs to happen. What are your biggest disappointments about the art community, and how are you using your work to ignite purposeful discourse?

KCM It’s difficult, I think, to talk about the broader art world beyond my immediate community in which I have found enormous support. I think, I would have to say that the disappointments I feel related to the art community (or communities, because there are so many) would be the ways in which they mimic the general population’s discomfort around identity. Generally, people have difficulty identifying with others across gender/race/class/age etc lines. I’ve thought a lot about how if my nudes were clearly male or female there might be a completely different level of support. I am happy in the muddiest of waters, but that is not most of us. I think there is an air of exploration that is sometimes not actualized with real cross identification.

EZM How do you see your work fitting into n e w f l e s h?

KCM I am not a man or a woman; therefore, I cannot be gay or straight. I don’t need to believe those categories are not stable or contiguous, I am living in the gappy purple space between them. Queer.

The body provides the locus for many identities, while being outside the language of identity. I mean to say that dumb matter cannot generate the meaning behind identity constructs. We each have two bodies, one material and one that tethers us to the identity matrix. That second one is basically an image or a container of what our bodies mean to ourselves and to other people. It’s cultural, subjective, and mutable. I am interested in opening the written seams between proprioception and gaze, material and consciousness, being and naming. How does my understanding of my body in relation to the false gender binary apply to the rest of my experience? Because of my experience, I can see seams where others cannot.

KCM I am not a man or a woman; therefore, I cannot be gay or straight. I don’t need to believe those categories are not stable or contiguous, I am living in the gappy purple space between them. Queer.

The body provides the locus for many identities, while being outside the language of identity. I mean to say that dumb matter cannot generate the meaning behind identity constructs. We each have two bodies, one material and one that tethers us to the identity matrix. That second one is basically an image or a container of what our bodies mean to ourselves and to other people. It’s cultural, subjective, and mutable. I am interested in opening the written seams between proprioception and gaze, material and consciousness, being and naming. How does my understanding of my body in relation to the false gender binary apply to the rest of my experience? Because of my experience, I can see seams where others cannot.

︎

Efrem Zelony-Mindell is a curator, writer, and artist. Their curatorial endeavors include shows in New York City and North Carolina: n e w f l e s h, Are You Loathsome, Familiar Strange, and This Is Not Here. They write about art for FOAM, Unseen, DEAR DAVE, VICE, Musée Magazine, SPOT, and essays for artists’ monographs. Their first book n e w f l e s h, published by New York’s Gnomic Book, is now available. They received Their BFA from the School of Visual Arts.